Brian Flores’ Smoking Gun

Brian Flores’ racial discrimination lawsuit against the NFL was filed only a few days ago, but already it has spiraled throughout the league, causing questions about tanking, about the current coaching carousel, and about John Elway’s drinking habits. There will likely (hopefully) be a million other stories before the whole thing is through, but before we get to that it’s worth just looking at the lawsuit on its own terms. The 58-page court filing is worth reading in full, if you haven’t already.

It’s quite an unusual document: It contains plenty of the annoying legalese you expect in a court filing (“Defendants have acted on grounds, described herein, generally applicable to Plaintiff and the members of the Proposed Class, by adopting and following systemic patterns, practices and/or policies that are discriminatory towards the Proposed Class.”), but is also almost novelistic in its structure. It moves back and forth between the specific instances of discrimination and humiliation faced by Brian Flores, who was fired by the Miami Dolphins, allegedly for refusing to lose on purpose, and then strung along by the New York Giants after they’d already supposedly settled on a different coach, and the larger context of racism in the NFL. It includes not just the stories of sham interviews and erroneous text messages, which have gotten most of the headlines, but also the blackballing of Colin Kaepernick and the NFL’s recent “race-norming” scandal. I’m not qualified to comment on it as a legal argument, but for whatever it’s worth, it’s a pretty compelling read.

The difficulty for Flores’ legal team (headed by Douglas Wigdor, who has a long track record of high-profile employment discrimination cases), I imagine, will be connecting these two threads: the specific experience of Brian Flores, and the long history of racism in the NFL. Already, the Giants have denied the specifics of the allegations, and people are speculating about what kind of “smoking gun” might come out in discovery, specifically around the text Flores got from Bill Belichick days before his interview with the Giants: How did Belichick know who the Giants were going to hire? When did he find out? Who told him? Etc.

These questions are all interesting, and I’m sure they are important to Flores’ legal case. But in a larger sense they’re completely irrelevant. We have already have the smoking gun, right there on page 3 of the complaint, where it quotes the words of the NFL’s own Executive Vice President of Football Operations, Troy Vincent:

There is a double standard, and we’ve seen that . . . And you talk about the appetite for what’s acceptable. Let’s just go back to . . . Coach Dungy was let go in Tampa Bay after a winning season. . . Coach Wilks, just a few years prior, was let go after one year . . . Coach Caldwell was fired after a winning season in Detroit . . . It is part of the larger challenges that we have. But when you just look over time, it’s over-indexing for men of color. These men have been fired after a winning season. How do you explain that? There is a double standard. I don’t think that that is something that we should shy away from. But that is all part of some of the things that we need to fix in the system. We want to hold everyone to why does one, let’s say, get the benefit of the doubt to be able to build or take bumps and bruises in this process of getting a franchise turned around when others are not afforded that latitude? . . . [W]e’ve seen that in history at the [professional] level.

In other words, it is quite clear, to anyone paying attention, that Black coaches are treated differently than white coaches in the NFL. The complaint is full of data to this effect. Since 1978, only 16 NFL Head Coaches have been fired after winning seasons—but four of those 16 were Black (including Flores), even though only 17 Black Head Coaches have coached a full season, and the first Black Head Coach wasn’t even hired until 1989. Since 1994, 14 NFL Head Coaches were fired after one season or less; four of those 14 were Black, including two of the three who were fired despite going 8-8.

Even if we just limit the scope to the last month, we can see the discrimination at work. For the third consecutive season, the Black offensive coordinator of the best offense in the AFC, can barely get an interview; instead, the Giants hired the offensive coordinator of the third-best offense in the AFC, who is white. In Houston, David Culley was fired after one season for “philosophical differences”—supposedly either he or the team changed philosophies in the 12 months since he was hired.

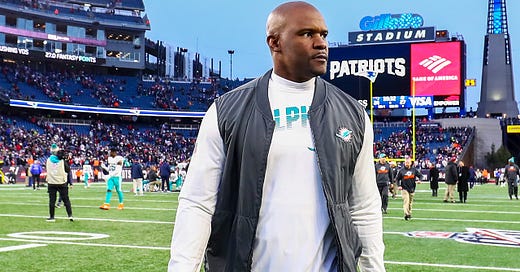

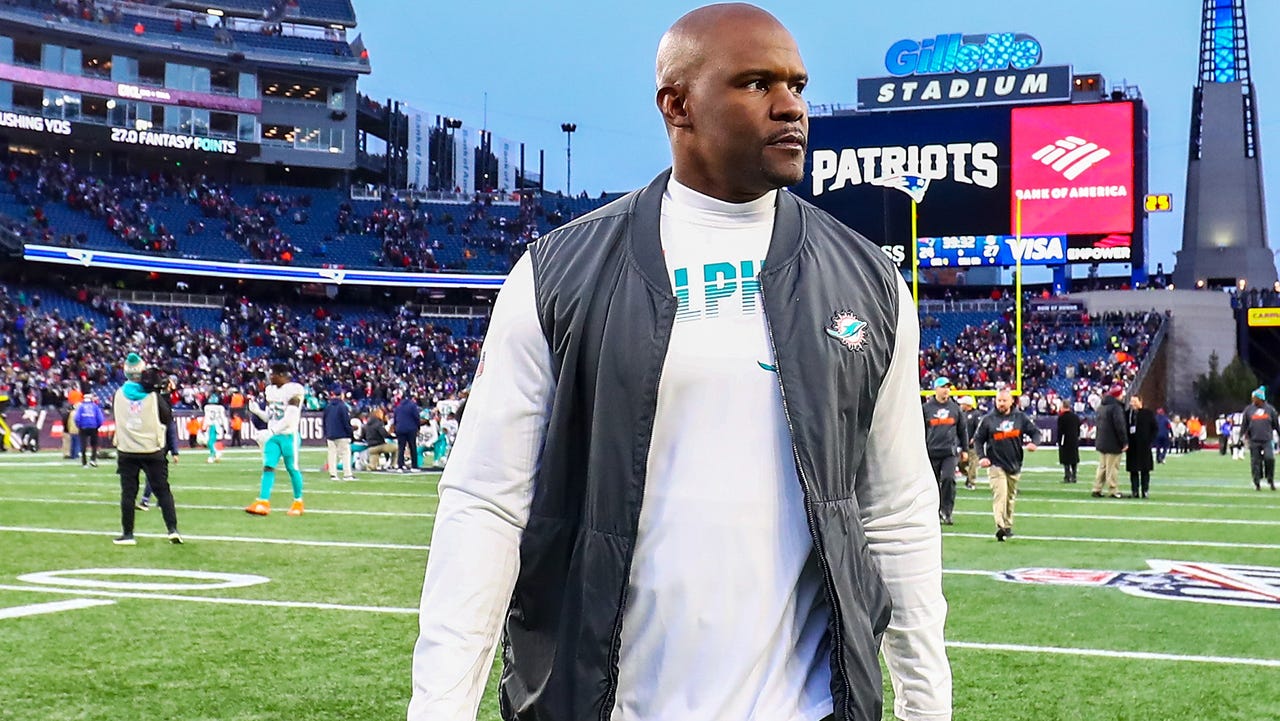

And then you have Flores himself, who was unexpectedly fired by Miami, even though the team won eight of its final nine games and concluded its second consecutive season with a winning record (the first time the Dolphins had back-to-back winning seasons in nearly two decades). The media immediately considered him one of the best coaching options on the market, if not the single most coveted. And yet a slew of inexperienced white coaches were hired ahead of him. And then he receives a text message that the Giants have decided to hire someone else before he even interviews.

What more evidence do you want to show that Black coaches are discriminated against? Black coaches take longer to get hired, are quicker to be fired, perform better than white coaches when they do have the job, but are held to a higher standard of success—what other smoking gun is necessary?

The temptation is to look for evidence that a particular decision, like the Giants’ choice of Brian Daboll over Brian Flores, is motivated by racial animus. Sometimes the law even requires that, so people go hunting for a different kind of smoking gun, like some hypothetical text message that reads “Hello, it’s me, the racist. Would you like to do some discrimination with me??”

But of course it never works like that, which is why it is mistake to look for racism in people’s hearts and minds and bones. Racism does not exist inside you—it exists in the external world. We should look for racism in the material circumstances facing Black people. And part of what makes this lawsuit so exciting is the way it puts those material circumstances in such plain language.

Reading the complaint, I could not help but think about baseball’s integration story, which followed a very similar trajectory. Specifically, I thought of how common it was for baseball teams in the 1940s and ‘50s to say, as the New York Giants said in their statement yesterday, that they were just looking for the best qualified candidates. “You’re not suggesting we sign a ballplayer/hire a coach JUST BECAUSE HE’S BLACK, are you? Surely we should pick the BEST PERSON FOR THE JOB—insisting on anything else would be SPECIAL TREATMENT and isn’t that the REAL RACISM??”

The defenses are identical, and if it sounds persuasive to you now, then you ought to consider what that means about whose side you would have been on then. If all the “best candidates” happen to be white, then perhaps there is something wrong with how we are defining “best.” That, more than the specific timeline of the Giants’ hiring process, is the real smoking gun.