Central Planning at the College Football Playoff

I really hate the College Football Playoff. Seemingly every year I find something new to hate about it. Luckily, though, I can usually relate these issues to socialism:

Anyway, this year I want to talk about “central planning,” that bugaboo of free market economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. To them, this is the cardinal sin of socialist economies. Talk about “central planning” conjures up images of corrupt bureaucrats in some private conference room making hugely consequential decisions without input or accountability from the public. Some people imagine the politburo in the Soviet Union. But I always imagine the College Football Playoff selection committee.

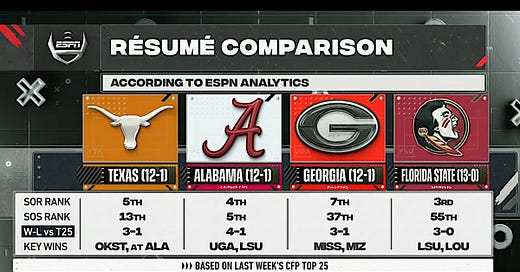

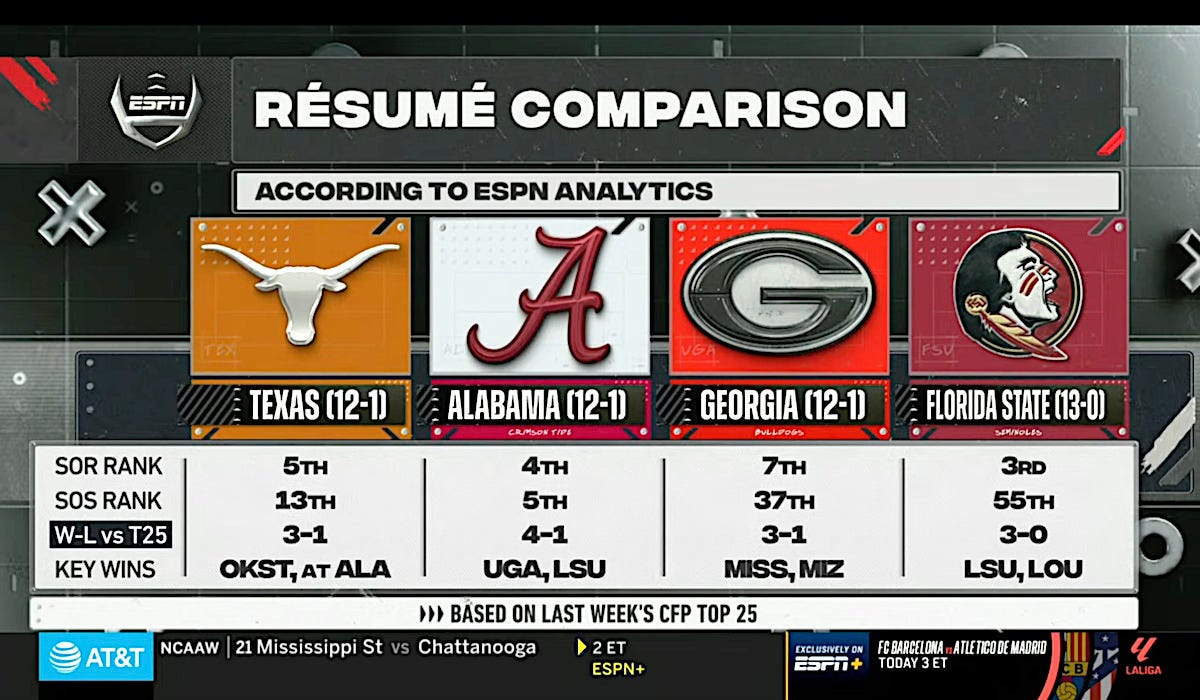

This weekend, the last four-team CFP was announced, with the committee selecting Michigan, Washington, Texas, and Alabama. As a result, for the first time ever, an undefeated Power Five conference champion, Florida State, will miss the playoff entirely. A lot of people were pissed off, for understandable reasons. What else could the Seminoles do, besides win all their games?

On the other hand, it’s not as if the choice was crazy. Florida State has not looked good since starting quarterback Jordan Travis broke his leg last month. Then they lost their backup, Tate Rodemaker Jr., last week, meaning they were forced to start their third-string QB, a true freshman named Brock Glenn, in the ACC Championship. The result was a rather lackluster offensive performance: The team gained only 219 total yards — over ⅓ of which came on a single run by Lawrance Toafili. Outside of that one play, the Seminoles hardly moved the ball, so I can see why the committee thought they weren’t one of the best four teams in the country.

Personally, I’m agnostic on the choice.* I haven’t watched enough college football this year to have a strong opinion of my own, and I’ve heard compelling arguments both ways. My objection is really to the audacity of the CFP committee thinking they can decide who “the best four teams” are. That is, technically, their remit, and every year we hear about the difficulty of choosing between the “best teams” and the “most deserving teams” — but it always strikes me as crazy that anyone can speak with any confidence about who “the best” teams even are.

*I have a general policy of rooting against Nick Saban. But I also have a general policy of rooting against Florida State, so I’m really at a loss here…

College football teams only play about a dozen games, with few common opponents. Teams that look great one week often look terrible the next. In such an environment, the idea that anyone has any authority to declare who “the best” teams are is absurd. It’s no wonder that the committee’s decisions are mocked year after year, and its rationale seems to change every week. The CFP committee is tasked with knowing something unknowable. So it can create a bunch of elaborate and opaque formulas and processes, but in the end it’s mostly guessing.

This is the problem faced by all “central planners” everywhere. And lest we think this phenomenon is limited to socialist economies and college football, it is actually quite common. Where does your credit score come from? Who sets interest rates? Where are highways built? They all come from central planners of one sort or another. Somewhere along the way, “central planning” got associated with communism, but it’s everywhere you look.

The thing that leads to central planning is not any particular economic mode — it’s a particular combination of imperfect information and entrenched hierarchy. Whenever that happens, central planners come up with all kinds of convoluted ways to use this imperfect information to justify the continued power of those in charge. In college football, we have no real way of knowing who the four best teams are (or 12 best, in case you thought this problem would go away next year), but there IS a clear hierarchy of college football teams: The SEC has never been shut out of the CFP, and so it’s not really surprising that Alabama made it over FSU.

One way to address this problem is to limit the inequalities that give rise to these hierarchies in the first place. But I actually think there’s something useful to be gleaned from the critiques that Hayek et. al. like to make of central planning in general, specifically about the hubris involved in the whole endeavor. I understand why some people respond to life’s randomness and unpredictability by trying to build a perfectly fair system. But it’s just not going to work. Instead, you should focus on making the system as clear and transparent as possible, while minimizing the harm of random unfairness.

In other words, if you’re going to have a playoff, you have to let teams play their way in. It’s silly to build a system that relies on a secret committee to “get it right.” Nobody could do that consistently. Instead, college football should adopt a system of automatic bids, where the criteria for entry into the playoffs is clear ahead of time. Just make a playoff that consists of the Power Five conference winners, plus three wild card bids handed to the highest ranked G5 teams. If that leads to a Florida State teaming playing a third-stringer in the playoff, then so be it. Life is unfair, but we can’t trust central planner to legislate unfairness like this out of existence. We should aim instead to build a system where everyone’s playing by the same rules.