David Ortiz, Steroid Panic, and the Moral Hypocrisy of the Carceral State

I was never going to be happy on the day David Ortiz made the Hall of Fame. As a Yankee fan who was alive between 2004 and 2013, Ortiz was involved in several of the worst moments of my life as a sports fan. I hated him when I was 16, and you almost never hate anyone or anything with more ferocity than the things you hate when you’re 16.

But in the years since Ortiz retired, I thought I had reconciled myself to the fact that he would inevitably make it to Cooperstown. For a while, I held out hope that his status as a full-time Designated Hitter might keep him out, but once Edgar Martinez was elected, I gave up even that pipe dream. Ortiz is simply too beloved. After he retired, he transitioned seamlessly from lovable player to lovable studio guy. And no matter how many times the idea of a “clutch player” gets debunked, fans simply refuse to give up the myth, and Ortiz’s playoff heroics make him the prototypical “clutch hitter.” So yesterday was a long time coming.

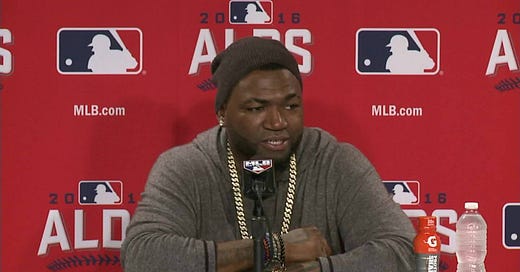

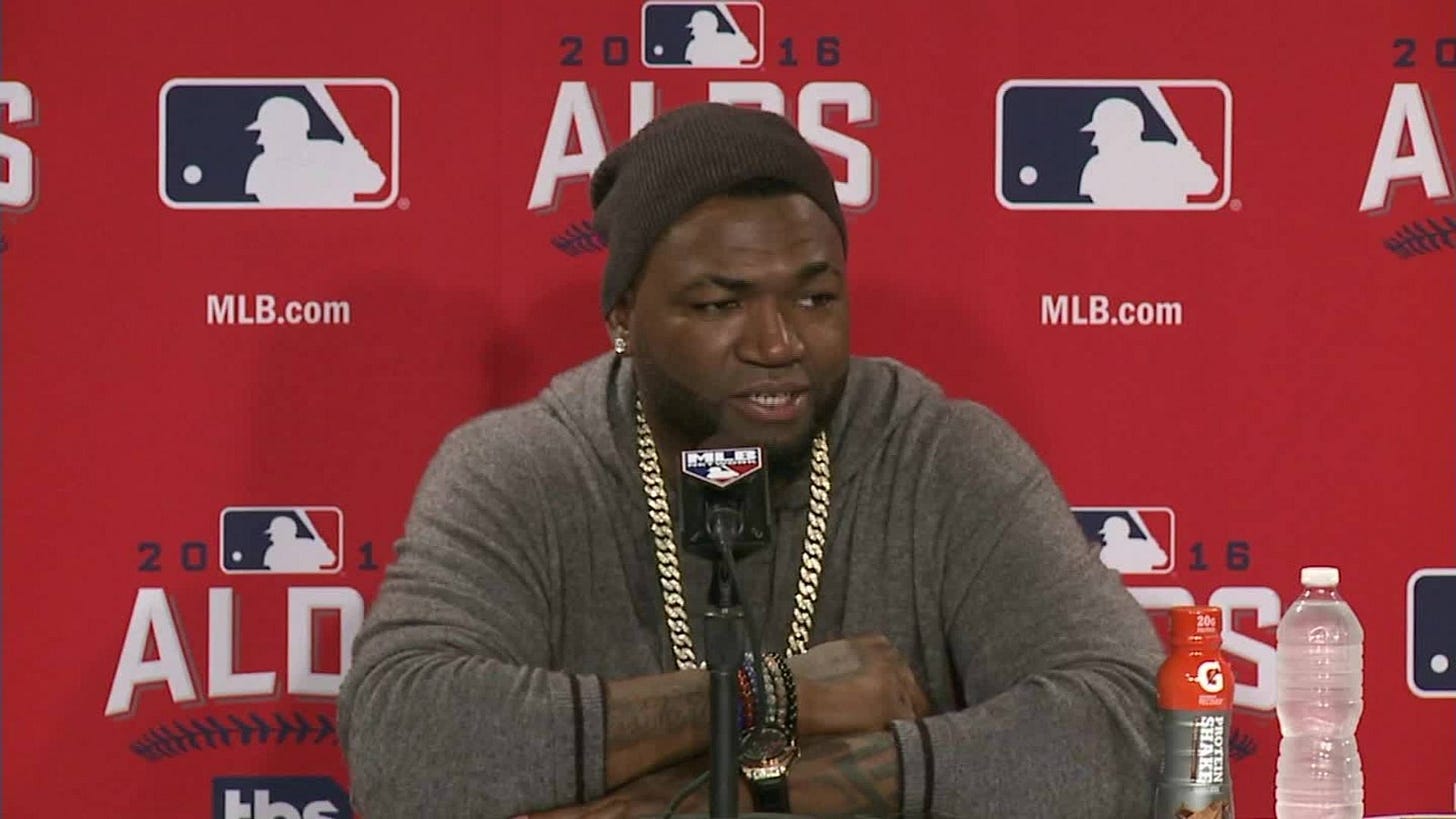

Which is why I was not prepared for the anger I felt. Obviously, some of that anger came from my own dislike of Ortiz, but it was mostly something else: the rank hypocrisy of baseball’s handling of the entire steroid era was on display in yesterday’s vote, and while Ortiz himself is not wholly to blame for that, he certainly seems to be the only one to benefit from it. Watching his big, dumb, smiling face thank the writers while a whole segment of the game’s history, and many far better players, is deemed unworthy of acknowledgement makes me want to throw up. Mostly because it makes me think about the 2004 ALCS, but also because it makes me think about America’s prison system.

Yesterday was a real milestone: David Ortiz is the first person known to have failed a steroid test to get elected to the Hall of Fame. This would be a momentous occasion if it represented a real shift in how Cooperstown and the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) treated suspected steroid users. But it doesn’t.

On the same day Ortiz was voted in, the BBWAA definitively and firmly shut the door on Roger Clemens, possibly the greatest pitcher ever, and Barry Bonds, probably the greatest hitter ever, because they are each alleged to have used steroids—even neither of them ever failed a test and both deny to this day that they ever knowingly used illegal substances. But the BBWAA has decided they are guilty, as it seems to have decided on the guilt of Alex Rodriguez, Gary Sheffield, and Andy Pettitte. But it has decided David Ortiz is innocent, even though he’s the only player mentioned thus far who actually failed a test for PEDs.

Let’s talk about this test, which often gets discussed with a kind of mysticism. In 2003, there was survey testing of MLB players to see if steroid use was indeed widespread: If more than 5% of players tested positive, then the league would institute a stricter testing policy (spoiler alert: they did!). The individual results were supposed to be anonymous, but David Ortiz’s name was among a list of several positive tests that were leaked in 2009. Ortiz himself has repeatedly insisted that he has no idea how he tested positive, once even blaming the positive result on a pro-Yankee conspiracy.

Normally, such denials from alleged steroid users are not taken very seriously by baseball fans or the media. After all, Bonds and Clemens have issued some of the most vehement denials—and both testified under oath that they didn’t use steroids—but nobody takes them seriously. And yet, people seem to believe Ortiz. Even MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred came out and said there was reason to believe Ortiz, telling the press in 2016, “Even if your name was on that list, it’s entirely possible that you were not a positive.” He pointed out that there were problems with “at least 10” tests (elsewhere he said “10 or 15”) that were never verified because all that mattered was that the total exceed the 5% threshold, and those contested tests were not necessary for those purposes. So there IS some uncertainty around Ortiz’s test.

But still, people talk about that test as if it were Schrödinger’s Cat. Last night, upon Ortiz’s induction, Joe Posnanski dismissed the test by writing, “Ortiz, based on an illegally leaked drug test from 2003, might have used and might not have used and there’s really no value in going any deeper than that.”

Hmm... really? A positive test from 2003 may not be proof, but does it really leave us as existentially uncertain as “might have used and might not have used”? Even if 15 of the 104 positive tests were false positives, that still leaves an 85% chance that Ortiz’s was one of the legitimate positives.

But if we’re just throwing out the whole batch, has anyone told Alex Rodriguez, whose name was allegedly on the same list, but does not get the benefit of the doubt that Ortiz gets? Has anyone told Sammy Sosa, who was also on the list and never got more than 18.7% of Hall of Fame vote in ten years, despite a resume eerily similar to Ortiz’s (but probably slightly better)? Sosa hit more career home runs, had a higher WAR, and he, like Ortiz, never failed a drug test after 2003, was never tied to BALCO or Biogenesis, and was not named in the Mitchell Report. But Sosa is widely assumed to have used steroids, even though the evidence against him is basically identical to the evidence against Ortiz.

So why does David Ortiz get the benefit of the doubt? What makes him so fucking special?

As Chad Finn wrote in the Boston Globe this week, in another piece that whitewashed his associations with PEDs, people just like the guy. He was “a big-swinging, home-run-blasting, larger-than-life October icon with enough charisma to light up the entire ballpark on the darkest night.” This might seem like merely a subjective thing, but the urge to turn gut feelings into empirical realities is strong.

It is, ironically, the same thing that benefitted Ortiz as a player, granting him the status of the mythical Clutch Player. Fans remember the big hits and walk-off home runs and his great October runs, and they ignore the totality of the evidence that suggests he was basically as good in the postseason as he was in the regular season.* They forget the 2013 ALCS, when he was 2-for-22, or the 2008-09 Division Series, when he combined to go 5-for-32.

*David Ortiz’s career slash numbers:

REG SEASON: .286/.380/.552

POSTSEASON: .289/.404/.543

When Alex Rodriguez had two bad Division Series in a row, it cemented his reputation as a choker. Who can say why that perception clung to him, and opposite clung to Ortiz, even though the numbers don’t bear out either conclusion. It all really just comes down to vibes. Guys like Bonds and Clemens and Sheffield and A-Rod give us bad vibes, so we believe the worst about them. Tellingly, all these guys were killed for not being clutch enough even before they were tagged as steroid users. But a guy like Ortiz has good vibes, so not only does his clutch-ness transcend a bad playoff series or two, but his moral purity transcends the actual evidence against him.

In September 2014, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral arguments in Barry Bonds’ motion to dismiss his conviction for obstruction of justice. A jury had deadlocked in the perjury case against him for his testimony that he did not use PEDs,* but had convicted him of obstruction of justice, not for making false statements under oath, but for making statements that were true but misleading. The arguments got kind of metaphysical, about whether and how you can mislead with the truth, but the government’s position was clear: Bonds had obstructed justice by saying things that, while technically true, were designed to mislead the court and cover up incriminating facts.

*An outcome widely reported as a “technicality” in the sports media. Once again, nobody considered the failure of legal case against Bonds as evidence in his favor.

At some point in the oral argument, though, a member of the panel interrupted the government's lawyer and said (I’m paraphrasing) “You realize everyone does that, though, right? Practically the whole legal system is people making true statements designed to cover up incriminating facts.” The judge even made a joke about how, if the court were to accept the government’s logic, they would have to lock up the entire San Francisco bar. His question really gets at a central contradiction within our legal system: There is a wide range of actions that would consider obviously illegal if some people did them, but are totally accepted if other people do them.

Just two years after Bonds’ criminal trial for perjury, the Director of National Intelligence James Clapper directly lied under oath about the targets of American surveillance. First, he claimed that he gave the “least untruthful” answer he could. Then, even more improbably, he claimed he simply forgot about the existence of a massive surveillance program he oversaw. As absurd as such answers are, Clapper was never charged with a crime, and was not even forced to resign. To this day, people will defend him, reaching desperately for excuses like a Hall of Fame voter looking for a reason to ignore Ortiz’s PED test. Because Clapper is not the kind of person to whom the law applies—he does not have criminal vibes.

If you do have criminal vibes, then the American justice system is a very different experience. If, for whatever reason, you do not strike people as sympathetic—maybe it’s your race or religion or class or mental health status or previous exposure to the criminal justice system or your job or any number of variables—then you will not be granted the nuance, the benefit of the doubt, or the infinite excuses afforded to someone as venal but upstanding as James Clapper

David Ortiz is not exactly James Clapper. But when I see people making excuses for him, I see the same phenomenon at work. Ortiz’s defenders are much like Clapper’s in the way they pat themselves on the back for their nuance, their judiciousness, their fairness, their open-mindedness. They talk about how complicated this particular case is, and how hard it is to be certain. But they would never think to be as generous towards people they don’t already like. It is the same moral hypocrisy at the heart of America’s cruel carceral state.

Who gets the benefit of the doubt, and who doesn’t? Who do we make excuses for, and whose excuses won’t we even take seriously? That’s really what this is about. Ta-Nehisi Coates has often defined racism as “broad sympathy towards some, and broad skepticism towards others”; I like that definition, but the Hall of Fame vote shows it is not limited to discrimination based on race. Ortiz is not benefitting from a racial bias, but a bias peculiar to the sports world, based on whatever strange mix draws fans to some athletes but not others.

Sometimes you like someone and want to think the best of them; sometimes you hate someone and want to think the worst. If that were all that were happening, it would be fine. Maybe the Hall of Fame should have different standards for players who were especially beloved and magnetic. But people can’t help but assign moral value to our biases. It’s not enough to like David Ortiz—we have to find reasons to say he Morally Good. And the league has now arrived at a moral code perfectly adaptable to whatever we already feel about a player. A positive test doesn’t make you guilty; a negative test doesn’t make you innocent. It’s all just vibes.

This urge to assign a moral value to vibes might seem like harmless fun when it comes to the Hall of Fame, but its real-world consequences are profound. Just look at our prison system. Very bad vibes there…