I’ve been thinking a lot about pitch framing recently, mostly to try and figure out how good JT Realmuto is. Realmuto is maybe the most sought after free agent in baseball this offseason, and possibly the best catcher in the game. But evaluating catchers right now is tricky because of pitch framing.

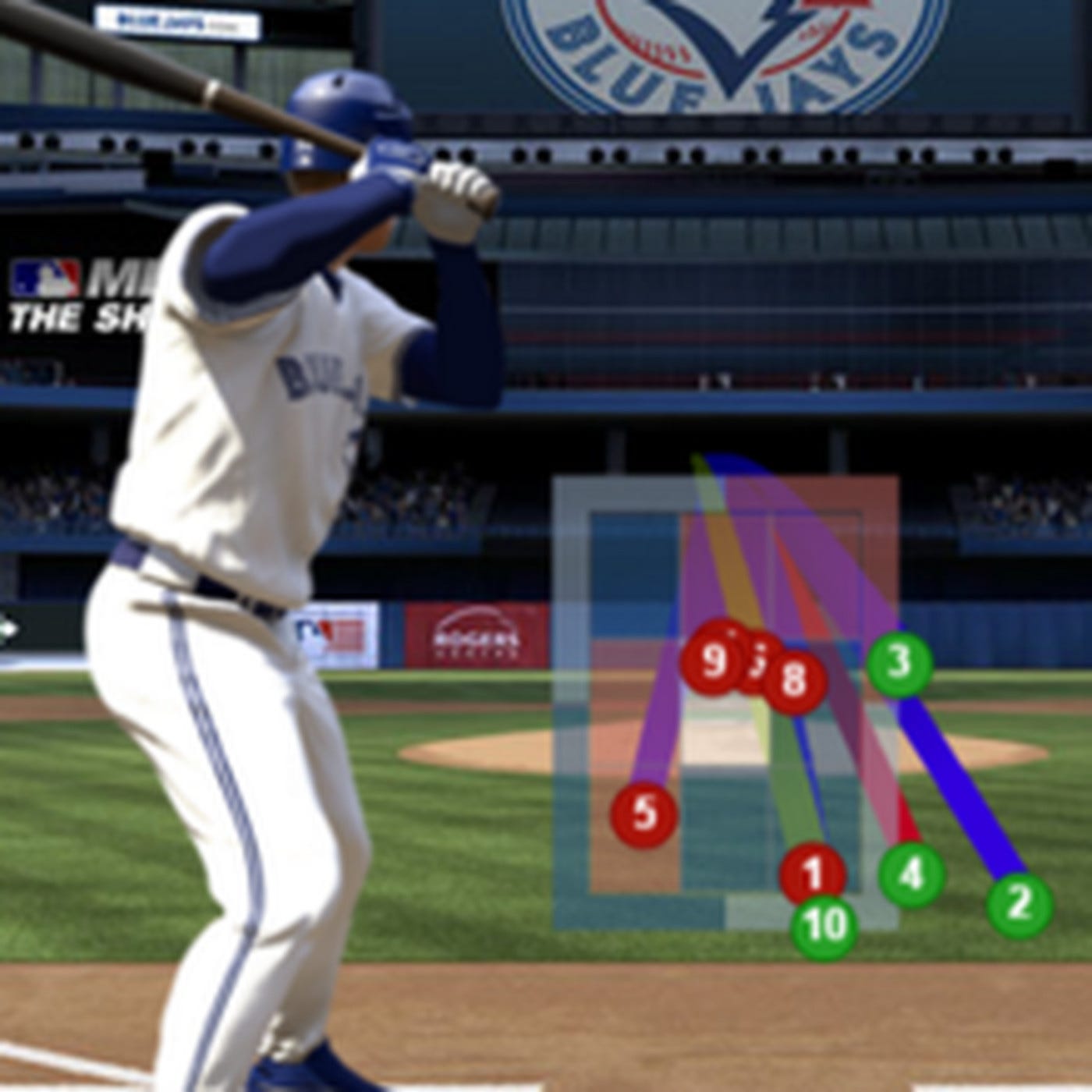

A little over a decade ago, nobody really talked about pitch framing—at least not in any way that could be quantified. But since the PITCHf/x system started yielding data, around 2008-09, the statistic has had a whole boom/bust/recovery cycle. Once scouts and analysts could definitively detect differences among catchers in how often they got certain pitches on the edge of the strike zone called as strikes, it seemed to become the most important way to evaluate a catcher’s defense.

Prior to 2019, Realmuto’s framing was enough to take him from the best catcher in baseball to out of the top five—the fact that his framing improved so much in Philadelphia seems to be a big part of why he’s so coveted this offseason. This year the Yankees altered Gary Sanchez’s catching stance to emphasize framing, resulting in a return of the problems he’d previously had blocking pitches. Based on what the organization said publicly, they were fine with the additional passed balls and wild pitches—and the ensuing criticism directed at Sanchez—so long as his pitch framing improved. That was how important they saw the skill.

But it’s not clear that the skill should exist at all. A strike is supposed to be a strike: It’s defined explicitly in the rules and not contingent on how, or even if, the catcher catches the ball. Of course, that’s never how it works in practice. Umps are human and fans recognize that they don’t call the literal, rulebook strike zone. Technically, the strike zone is supposed to go from “the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and top of the uniform pants” (usually called “the letters”) to the “the hollow beneath the kneecap.” But nobody really calls it that high, and some don’t go that low. There is variance between umps and between eras. In the 1990s, before QuesTec, umps gave a few inches off the edge of the plate—famously benefitting the Atlanta Braves staff and, for one afternoon, Livan Hernandez.

People refer to this, both positively and negatively, as the “human element,” but human fallibility is not the only factor. It also reveals a basic truth about rules—that they are defined not by their literal meaning, but by their enforcement. The strike zone is not really what the rulebook says; the strike zone is whatever the umps call strikes.

This isn’t just true for sports. Take a seemingly simple question: Is marijuana illegal? Well… it’s complicated. Technically, it’s illegal under federal law, according the Controlled Substances Act, which defines it as a Schedule I drug—the same as heroin. But many state and local governments have decriminalized it, or legalized it outright, and the federal government has deferred to them in most cases—though the DEA still does arrest people for it. So, it’s sort of legal some places in the US, and sort of illegal everywhere.

Of course, what most people really mean when they ask a question like that is: What will happen to me if I get high? And that has always been a very loaded question. For as long as I’ve been alive, the answer is pretty bifurcated: If you’re a white kid in a college dorm room, you’ll be fine. If you’re a Black person or a public housing resident or in any number of other vulnerable situations, it could ruin your life. And just as pitch framing can turn strikes into balls and balls into strikes, enforcement can make legal behavior illegal just as easily as it can make illegal behavior legal. There is no law against driving around with large sums of cash in your car, but if the police deem you suspicious, they can just take your stuff.

Note that the issue here is NOT just the “human element.” If the criminal justice system’s mistakes were merely the result of human error, and therefore distributed randomly across the population, it would not generate the same social outrage. The issue is that the biases are predictable and systemic, repeatedly favoring some groups over others.

Similarly, it is not just umpires miss calls. It’s that pitch framing has revealed that their misses are so consistent and predictable that they can be gamed by catching the ball in a certain, favorable way. Indeed, as teams have caught on and emphasized those skills, the gap between the best framer and the worst has narrowed considerably as bad framers either improve or lose playing time. This is almost normal, except that most athletic skills are not contingent on a quirk of enforcement. If robot umps were installed tomorrow, home run hitters would still hit home runs, base stealers would still steal bases, and hard throwers would still throw hard. But pitch framing would cease to exist. This is why it feels like an unnatural skill to reward. If the only solution is robots calling balls and strikes, then I guess we need to defund the umps.