It's now been about three months since I first started writing about baseball’s integration, in a post that was originally designed to be a few hundred words about Elston Howard. Instead, it’s sprawled into ten separate posts, totaling over 20,000 words. I’m probably going to take a break from this subject after this one, but today I wanted to go over two final big picture takeaways I had.

6) This is not really a success story.

The desegregation of baseball is generally seen as a triumphant moment in American history. It’s not just that Jackie Robinson—and baseball’s “great experiment”—succeeded, but the way that success was achieved. Baseball was not integrated by a court order, or legislation, or even by disruptive mass protest. It was just one enlightened gatekeeper opening the door and a seemingly natural meritocracy taking hold. It’s a comforting story in the way it suggests that systems can fix themselves.

Of course, I would not have started this series had I not been a little a skeptical of that story. Nevertheless, I was surprised by the way it fails even on its own terms. The idea that the success of Robinson and Co. paved the way for future Black players is enshrined in baseball lore—but it requires sanding away a lot of inconvenient details. Because despite the immediate success of Robinson in 1947—plus Larry Doby and Satchel Paige in 1948, Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella in 1949, Sam Jethroe and Hank Thompson in 1950, etc.—it still took SO LONG for other teams to add Black players.

It's not just that the last team didn’t integrate until 1959. That’s a familiar fact, but it could be explained by a single recalcitrant owner. It’s also about the fact that only a single team added Black players between 1948 and 1949. If it were simply a matter of teams waiting to see how Robinson performed, then you would expect the dam to have broken after his spectacular rookie year.

But perhaps I’m being too impatient. After all, it takes time to scout and develop players, and Robinson had a whole year in the minor leagues. So maybe teams just needed more time. Well, a full seven (seven!) seasons after Robinson’s debut, half the teams in the league had not integrated. In that time, Black players had won the Rookie of the Year every single season in the National League. Their ability to succeed at the highest level had been proven many times over—and yet discrimination persisted for years.

Even the 1959 date is misleading, since it only counts how many teams had a single Black player, and not the proportion of roster spots held by Black players in total. In fact, it wasn’t until 1965—18 years after Robinson’s debut and nine years after he retired and three years after his induction into the Hall of Fame—that the percentage of Black players in the MLB matched their percentage in the overall population.

And, as I’ve tried to hammer home throughout this series, every year of delay covers a million tiny tragic stories. Players forced to live in isolation because a team wouldn’t stop booking segregated hotels on the road. Careers cut short because a racist manager got hired. Lives put on hold because a team wouldn’t call someone up from the minors. Etc. A whole generation of baseball players was caught up in this prolonged delay. When you go through the players featured in this series, there are very few stories with happy endings.

Optimists like to insist that time is simply a necessary price to pay for the transition to a more just world. They will acknowledge that the delay is sad but maintain that it is unreasonable to expect things to change “overnight.” Instead they will take the long view, pointing out that, by the 1970s, Black players were actually overrepresented in professional baseball; that decade also saw the first Black manager and GM. Maybe it took longer than it should have, but it worked out “in the end.”

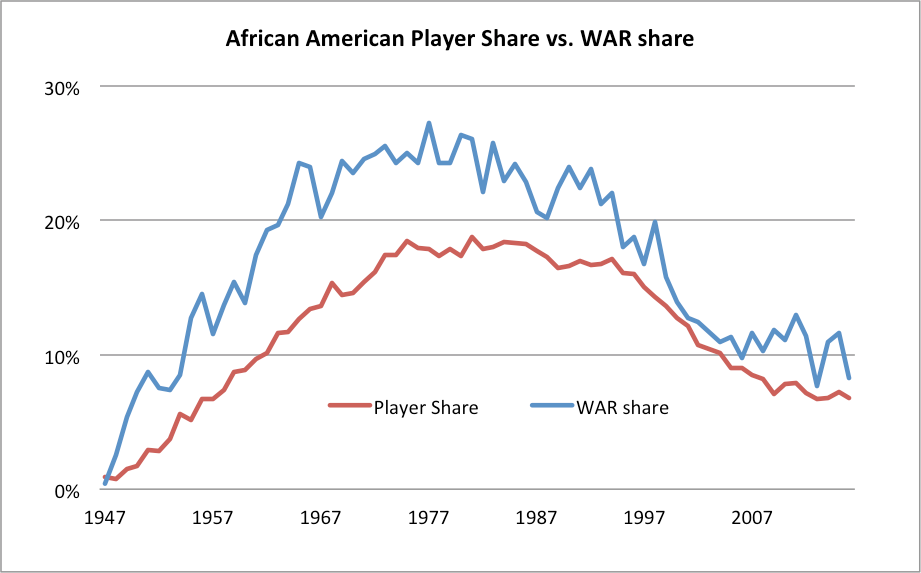

Except there is no “end” to history. What if we take an even longer view? Around 1995, the percentage of Black players in baseball started to decline. By 2000, they were underrepresented once again, and the number has remained low ever since. In 2020, Black players made up about 7.8% of roster spots—or about the same proportion they held in 1958, before two teams had even integrated. They have never reached proportional representation on coaching staffs, or in front offices, or among owners. It is hard to take the arguments for patience seriously when things are so clearly moving backwards.

When you look at the details, baseball’s integration is only a success story if part of your definition of “success” includes not challenging the power centers of baseball. And indeed, by that measure it is truly remarkable that baseball added Black players with such little disruption. But is the absence of disruption more important than fair treatment? The progress Robinson initiated has stalled or gone backwards. Indeed, according to a report in the Society of American Baseball Research, Black players have always made up a higher proportion of total WAR than total roster spots—suggesting there was never a time when they didn’t have to be better than their white counterparts.

If that’s not a condemnation of the “Let systems fix themselves” argument, then I don’t know what is…

7) Was there another way?

If the integration of baseball was not a success, then what would success have looked like? This question has been haunting me throughout this project. Any answer is likely to be a little unsatisfying, necessarily relying on speculative counterfactuals. But it seems important to offer a viable alternative theory of change. After all, it’s not as if unambiguous success stories are easy to find in the civil rights movement. School segregation persists nearly 70 years after the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in Brown. Voting laws continue to target minority voters, 66 years after the Voting Rights Act. And the racial wealth gap has barely budged since 1968. So, is it even reasonable to suggest that baseball could have done any better?

I think so, and I think a hint can be found in, of all places, Larry MacPhail’s letter, which you may remember as the Quasi-Official Defense of Segregation from 1945. MacPhail spends much of the letter bashing the Negro leagues, insisting that they are too poorly run to be taken seriously and that white baseball cannot integrate until Blacks sort that all out. He wrote:

“If and when the negro leagues put their house in order – establish themselves on a sound and ethical operations basis – and conform to the standards of Organized Baseball – I favor admitting them to Organized Baseball; and the rights, privileges, and obligations of such membership. This would serve to give the negro leagues greater prestige; help stabilize their operations; and protect the rights of their public and players.”

It's pretty clear, given the context, that MacPhail is trying to slough responsibility for segregation off of “Organized Baseball” and onto the Negro leagues, blaming them for the problem and insisting that any solution has to start with Blacks “put[ting] their house in order.” But he is still providing a path towards integration, and one that could have kept in place many of the structures of Black baseball. (Tellingly, this part of MacPhail’s letter was not included in the report issued by the league the following year, which included other parts of that letter verbatim.)

You could imagine a version of MacPhail’s plan that was stripped of its racial paternalism. In this scenario, baseball would have entered formal relationships with Negro league teams and used them as developmental leagues. There is certainly something paternalistic to reimagining the Negro leagues as a farm system for white baseball, but of course that’s ultimately what happened anyway. By making the arrangement formal, a role could have been preserved for Black coaches and managers and scouts. Rather than watching as the Negro leagues simply crumbled away, you could imagine a future for them like that of the Pacific Coast League or the Mexican League, both of which eventually transitioned from near-major leagues that had monopolies on certain regions or players to long-term minor leagues.

Why would this have been better? When recalling the Negro leagues, it’s important to neither romanticize them nor dismiss them. On the one hand, the teams were often poorly run, and players treated badly. Jackie Robinson and many others were not sad to see them go, as the owners often took advantage of the fact that Black players had few other options. Indeed, many Negro league owners feared integration, recognizing it as an existential threat to their existence.

On the other hand, the Negro leagues offered Black players an opportunity to succeed without having to conform to white standards. Most players recalled their years in Black baseball very fondly, and the teams provided more accepting environments, particularly for marginal players and coaches. Traditional white minor leagues, being disproportionately located in the South, were often inhospitable to Black players—particularly after the backlash to the Brown decision, when integrated minor league teams became convenient target for revanchist politicians and white terrorism. Leaving the Negro leagues in place, and giving them an official status within “Organized Baseball,” would have been a way to combat those difficulties.

This is a common tension whenever discussing Black enterprises that arise in the face of discrimination—you still see it in discussions over “Black-owned businesses.” Such enterprises address a real need, and they are often the best way for Black people (or people in any minority group) to advance in a particular trade or profession. But Black capitalists are still capitalists, and often more predatory than a typical business, since they are serving a captured clientele. It makes sense to build up Black institutions, but Black owners are not really worth protecting.

Indeed, it was in many ways the owners’ short-term focus on their bottom lines that prevented them from pursuing this route until it was too late. As early as 1943, people like Wendell Smith advised Negro league owners to have a plan for when white owners and executives inevitably started raiding their leagues for talent. Instead, Black owners focused on making sure that they were compensated by MLB teams who purchased the contracts of Negro league stars. When two Negro leagues did eventually submit a written application for formal recognition in 1947, they were rejected. White baseball was not eager to them any favors, content to simply poach players individually as the independent leagues struggled to stay afloat. For many players too, the demise of the Negro leagues was no great loss, at least in the short-term. After all, Organized Baseball offered more stable employment, better pay, and the chance at greater recognition and competition.

But the loss of the Negro leagues left Black players at the mercy of white gatekeepers, which led to the prolonged and perpetually incomplete nature of integration. Preserving the Negro leagues in some form—not to protect the wealth of Black owners, but as a way of letting Blacks continue to govern themselves as the MLB integrated—would have been preferrable. Successful integration would have included the integration of gatekeepers, which typically means building up independent institutions, not tearing them down. The Negro league example shows how hard it can be to do that when those institutions exist primarily for the enrichment of an ownership class.

***

In all the words I’ve written on this subject, there’s one thing I never found a place to discuss: the beanballs. Stories about Black players getting thrown at in the early years of integration are plentiful. There are famous stories about Robinson having to hit the deck, and less famous stories about minor leaguers getting sent to the hospital. Curt Roberts, who got credit for desegregating the Pirates, set a minor league record for hit-by-pitches, and then was hospitalized by another beanball the following year.

It's hard to find hard data on this—plenty of early Black players led the league in HBPs, but a lot of that was Minnie Miñoso, who was known to crowd the plate—but it was certainly conventional wisdom that Black players got thrown at more than whites. “As soon as you walked up there, you’d get knocked down,” according to Bob Thurman, an early Yankees prospect who eventually played a few seasons in Cincinnati. It was a sad reality, but one the players could get over: “I was knocked down in the Negro Leagues so much, this didn’t bother me,” Thurman said.

Stories like this show that there’s no need to be overly cynical or morose about the early days of integration. Obviously, the beanballs—and all the other petty interpersonal humiliations, from the taunts to the inadequate lodgings and segregated meals to the long stretches in the minors—were unacceptable, and it’s unfair people had to endure them. But people are pretty resilient, and they can overcome being mistreated.

Indeed, to the extent that there IS a success story in the story of baseball’s integration, it is in these personal triumphs over discrimination. Because the worst did not happen: Fans did not revolt or abandon the game; racist players did not boycott; integrated teams did not crumble in the face of internal divisions. In all cases, the outcomes were closer to the opposite: Fan interest in the game increased; racist players learned to get over it; integrated teams played better than teams that clung to segregation.

But if this story shows the capacity of people to triumph over personal bigotries, it also shows the limitations of those triumphs. Because as good as Robinson and the Dodgers—and Doby and the Indians, and Mays and Giants—were, that couldn’t overcome the institutional obstacles that kept power in baseball racially stratified. No matter how many hearts and minds Robinson and Co. could win, it was not enough to challenge the structural racism at the heart of the game.

Sometimes I worry that we’ve learned the exact wrong lesson from racism’s persistence. I worry that people’s takeaways from the police killings of George Floyd and others is that people are just hopelessly racist, and that the way to defeat racism is to constantly look inward, always on guard against secret racist feelings you might have buried deep inside you. But if the history of civil rights—and the history of baseball—shows us anything, it is how flimsy people’s personal bigotries really are. Pitchers would throw at Black players, but then those players would steal second, or hit a home run, and the pitchers would move on to trying to get them out. Racist players who resented Black teammates would become the first to defend them if an opposing player spiked them. Fans in notorious racist cities quickly embraced players who helped their teams win. No matter how embedded racism might seem, people’s personal feelings are just more fluid and complex than we give them credit for.

The problem is that these feelings aren’t enough when you don’t have power. The answer is not to look inward, but outward, at the material systems that determine who has power. The answer, as always, is socialism.