If you missed Part One from last week, check it out here. There will be at least one more installment…

4) Race is a social construct.

I mean, obviously, right? At this point, that’s such a cliché that it’s easy to forget what it means in practice. But when you’re trying to list the first Black player for every baseball team, you very quickly run into the artificiality of these categories. Blacks from Latin America like Carlos Bernier, Ozzie Virgil, Carlos Paula, Chico Fernández, and Minnie Miñoso did not fit neatly into any one box. Sometimes they were considered a team’s “first Black player” and sometimes they were not—I hoped some kind of logic for who counted and who did not would emerge, but it really seems to have been a case-by-case kind of thing. Sometimes it was about skin tone, or how a player identified personally. Some said they were black but didn’t identify as “Negro”—but of course usage around those terms themselves has changed since then, so it’s hard to know what to make of such distinctions.

It's an obvious point, but it’s always worth reflecting on the fact that races are just categories. And like any categories, they are helpful sometimes, but not always. You will always get examples that don’t fit neatly in any one box, but that doesn’t mean the categories themselves are not useful.

Sometimes people interpret “race is a social construct” to mean “race isn’t real” or that people can simply ignore or opt out of these divisions. But baseball’s story shows how futile that line of thinking is. Just because the racial divides are socially constructed categories that can change over time and be porous at the borders doesn’t mean there wasn’t a clear effort to bar a whole category of people from Major League Baseball. Nor does it mean that such an effort could be defeated by ignoring race or insisting those divisions weren’t real. Indeed, defeating segregation took collective action by people who were not only aware of their racial identity, but prioritized and valued it as a way of forging solidarity.

5) The excuses really don’t change.

I have this problem: Despite my cynicism, I do believe that our society has made progress on racial issues, and I always expect to see that progress apparent in the racial attitudes of previous generations. I’m always looking for explicit racism in their thoughts and feelings, half-expecting to read people in power saying things like, “Oh yeah, we’re big racists. We love racism and our main thing is doing racist stuff to people.”

But, for the most part, nobody really says stuff like that. In fact, people in history sound remarkably like people today. One of the funnier aspects of this project was how often people in baseball made arguments that are almost identical to arguments you might hear today in defense of some racial disparity. Let’s quickly go through some of them:

It’s not racist; Blacks just aren’t good enough.

This one is important because it is the most obviously ridiculous, but also may have been the most common excuse. Throughout the segregation era, baseball figures like Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis would point to the lack of any specific rule barring Black players as proof that their absence was purely a matter of merit: Teams were free to play Black players if they really thought those players could help them—the fact that they didn’t was just a result of Black players not earning their spot.

It's easy to read things like that now and assume they were lying. That they secretly knew Black players were good enough and were just trying to hide their discrimination. After all, the fact that Black players like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Monte Irvin, Sam Jethroe, Roy Campanella, and Willie Mays immediately became some of the best players in the league would certainly seem to make a mockery of the “They’re not good enough” argument.

But “lying” is probably the wrong way to think about it. Instead, they were merely defining “good enough” in a way that inevitably excluded Black people, whether intentionally or not. One common tactic was to denigrate the Negro leagues, insisting that they were poorly run and that the teams were therefore undisciplined and not conducive to developing pro players. And there was some truth to this: Given the economics of Black baseball, the teams often ran on shoestring budgets, which meant players missed paychecks and sometimes quit or left for more stable employment midseason. The league structures were very ad hoc, making it hard to tell whether games were exhibitions and what players’ statistics really were.

And so it was easy for people to convince themselves that players who succeeded there could not necessarily translate their success to white baseball. It wasn’t a matter of them lacking talent—it was a matter of insisting that Major League Baseball required more than just talent. Even after Bob Feller put together his famous 1946 barnstorming tour with Satchel Paige, he insisted that there wasn’t a single Negro league player ready for the MLB (although he may have said this as part of his rivalry with Paige—Feller was known as kind of a dick).

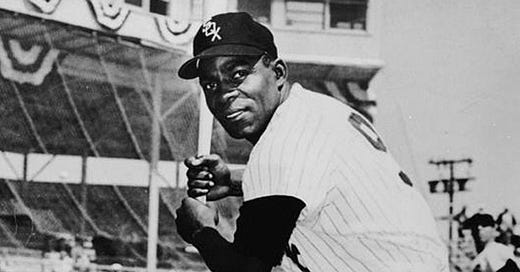

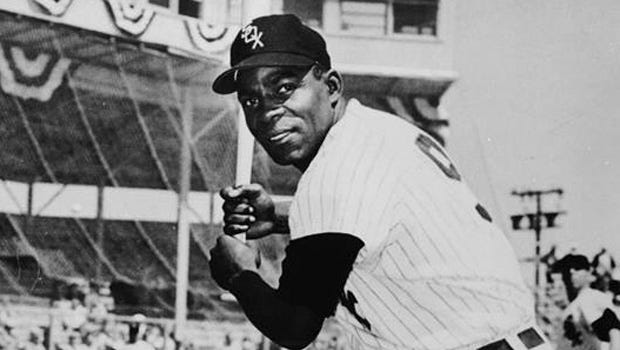

Indeed, the initial response to the success of Robinson and Co. was to acknowledge their talent, but typically in a way that suggested it was raw and undeveloped. For example, it was common to talk about the speed these players brought to the game. Stolen bases had largely fallen out of favor in the 1930s and ‘40s, but guys like Robinson and Jethroe and Minnie Miñoso immediately became league leaders and brought the skill back. In focusing on their speed, though, people presented baserunning as purely a natural talent instead of a skill that these players had developed.

The implication was always that Black talent needed to be fostered by white institutions. In the series, we saw how guys like Elston Howard, Gene Baker, and Vic Power were kept in the minor leagues for years before finally getting a chance to thrive.

It’s worth reflecting on just how common this attitude still is. It’s not as common to say that “Blacks people aren’t good enough,” but people will insist that the reason Blacks (or other minority groups) are underrepresented in some competitive industry is that they lack the necessary qualifications. The reason there aren’t more Black judges is that there aren’t more Black law clerks, and the reason there aren’t more Black law clerks is that there aren’t more Black students in law schools, and the reason there aren’t enough Black students in law schools is that not enough Black people go to college and the reason not enough—OK, I’m going to stop here, but the point is that the problem is always somewhere else. There is always some quasi-meritocratic argument that takes away your culpability.

The obvious alternative is that if your evaluative standards are excluding Black people, then you need to change your evaluative standards. In the case of baseball, that would have meant accepting the Negro leagues as legitimate—but the Negro leagues died out in the years after 1947, and so baseball never had to do that. They just funneled everyone into the white-run minor leagues.

It’s not racist; Blacks are actually better off this way.

When a Boston City Council member challenged the Red Sox segregation policy in 1945, their GM Eddie Collins defended the team by saying, “We have never had a single request for a try-out by a colored applicant.” This may have been true: People are pretty good at picking up unwritten rules on their own, and surely most Black players realized it would have been a waste of time to try out for the Red Sox, as it was for the players who attended the show tryout Collins staged in 1945.

But this was, again, a common trope among people defending segregation. A 1942 editorial in the Sporting News insisted that Blacks and whites “prefer to draw their talents from their own ranks and both groups know their crowd psychology and do not care to run the risk of damaging their own game.” As proof, they would cite the mere existence of the Negro leagues as proof that the status quo worked for everyone. Defenses like this often amounted to some version of Nice separate league you’ve got there; it’d be a shame if something happened to it…

A theme of the MacPhail letter is that integration would threaten the Negro leagues: “The negro leagues cannot exist without good players… If the major leagues of Organized Baseball raid these leagues and take their outstanding players… the negro leagues will fold up… and a lot of professional negro players will lose their jobs.” The implication here is that that Black players as a group cannot succeed in “Organized Baseball,” and that only a few “outstanding players” will make it, at the expense of everyone else.

The idea that, absent external restrictions, Black players could compete and earn a commensurate proportion of playing time, is dismissed wordlessly. Instead, it is assumed that some secondary status is the only way for them to have any opportunity at all. Any threat to that secondary status might actually make them worse off, so better to not rock the boat.

We shouldn’t dismiss MacPhail’s letter, since what he predicted basically happened: Integration did ultimately kill off the Negro leagues, as it killed so many Black businesses in other industries. But I suspect most people would take that trade. We ought to be careful of the reactionary logic that says, Yes, the current system is bad for many people, but changing it in any way might make it worse, so we should preserve the status quo.

It’s not racist; it’s just a controversy invented by white communists to stir up trouble.

Related to the idea that Black people didn’t really mind segregation was the idea that it was only an issue because “outside agitators” had made it one. MacPhail’s letter is directly addresses this issue:

“It is unfortunate that groups of political and social minded drum-beaters are conducting pressure campaigns in an attempt to force major league clubs to sign negro players now employed by negro league clubs. Members of those groups are not particularly interested in baseball… They know little about professional baseball – and nothing about the business end of its operation. They have singled out Organized Baseball for attack because it offers a good publicity medium for propaganda.”

It is impossible to read that and not hear echoes of modern accusations that Black Lives Matter protesters are “exploiting” police shootings for a “far left” agenda.

But we can go even further, because defenders of segregation were not always so vague about “social minded drum-beaters”—they were often explicit about naming communism as the force leading the charge. And they were right! The American Communist Party was one of the few institutions in the country campaigning against segregation in the 1930s and ‘40s, both in general and in baseball specifically. This is an uncomfortable fact that liberals often like to suppress or ignore, preferring to think of desegregation as a natural development of American democracy. Often liberals will insist, like MacPhail, that communists only used the segregation issue “for propaganda”—as if it was unfair to make something like segregation about political power. But whether or not you believe it validates their larger critique of American democracy, the fact is that communists and radicals were morally right on this issue.

On the other hand, Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson were both avowed anti-communists who sought to de-emphasize the role of radicals in their story. When Joe Bostic, a Black sportswriter, showed up at the Brooklyn Dodgers 1945 spring training with two Black players wanting to try out, Rickey chewed him out and told Bostic he was setting back his own cause—if Rickey were going to integrate his team, he couldn’t be seen as doing it in response to a demand from Black people. It had to be an act of noblesse oblige.

And Robinson famously testified in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949, in an effort to distance Black Americans from communism after famous actor and singer Paul Robeson had praised the Soviet Union. Robinson’s testimony did almost as much as his on-field performance to cement him as an American icon—and is also part of why he is sometimes viewed with suspicion by the left. But it’s worth remembering what Robinson actually said. He was clearly ambivalent about being used to condemn another Black leader, and he took pains not to be overly critical of Robeson, only saying that his statements “sounded very silly to me.” He also made clear to insist that the real enemy was not really communism but Jim Crow:

“The fact that it is a Communist who denounces injustice in the courts, police brutality, and lynching when it happens doesn’t change the truth of his charges. Just because communists kick up a big fuss over racial discrimination when it suits their purposes, a lot of people try to pretend that the whole issue is a creation of communist imagination, but they’re not fooling anyone with this type of pretense, and talk about communists stirring up Negroes to protest only makes present misunderstanding worse than ever. Negroes were stirred up long before there was a Communist Party, and they’ll stay stirred up long after the party has disappeared unless Jim Crow has disappeared by then, as well.”

Of course, Robeson was still blacklisted after the incident. The singer did not blame Robinson for that, but later in his life Robinson would speak regretfully about his testimony. The former Dodger spoke admiringly of Robeson’s stance and conceded that “in those days I had much more faith in the ultimate justice of the American white man than I have today.”

The whole incident speaks to the double-bind figures like Robinson and other civil rights leaders always seem to face: In order to be accepted by mainstream Americans, they are pressured to condemn radicals, but at the same time, their experiences with the American mainstream tend to validate the criticisms offered by those same radicals.

It's not just that calls to denounce “radicals” or “the far left” are always cynical, but that they are part of a persistent effort to drive a wedge between socialism and civil rights. Even when Black radicals are rehabilitated after their death and turned into American icons—as happened to Frederick Douglass and MLK and seems to be happening to Fred Hampton now—the socialist aspects of their messages always get sanded away. It reveals, I think, what messages are truly threatening.

It’s not racist; THEY’RE racist!

Perhaps the most obvious link between then and now is the attempts to shift the blame from institutions to people. Let’s revisit the story of Ben Chapman, which I wrote about briefly in the section on the Philadelphia Phillies. Chapman was the Phillies’ manager in 1947, and his vicious, racist heckling of Jackie Robinson in an early game in Brooklyn that year (“At no time in my life have I heard racial venom and dugout abuse to match the abuse that Ben sprayed on Robinson that night,” wrote the Dodgers traveling secretary) was a pivotal moment in Robinson’s rookie season. The taunting was so bad that teammates formerly skeptical of the Robinson experiment came out to defend him, and Branch Rickey saw the incident as helping to unite the team.

You’re probably familiar with this story—it’s a big scene in the movie 42 and features prominently in most stories about Robinson’s first year. Even at the time, it was a big deal. News stories from 1947 immediately latched onto the incident, and while there were some people who defended Chapman, insisting his taunts were part of the game and a way of welcoming Robinson to the big leagues (“In a weird way, it might have been racist NOT to heckle Robinson”), there was a quick consensus that he had crossed the line. Chapman was forced to apologized, saying he “would be glad to have a colored player” on the Phillies and a conciliatory photo op was staged with him and Robinson when the Dodgers went to Philadelphia in May.

Of course, Robinson wasn’t exactly thrilled about this, later writing: “I can think of no occasion where I had more difficulty in swallowing my pride and doing what seemed best for baseball and the cause of the Negro in baseball than in agreeing to pose for a photograph with a man for whom I had only the very lowest regard.” What Robinson seems to have understood is that baseball as a whole was very invested in the narrative of Chapman the Villain. An Alabama native, Chapman was known as a bully and an intense bigot—he had directed similar anti-Semitic taunts at Hank Greenberg in the 1930s. It was a very convenient story to say the real obstacle Robinson faced was the prejudice of men like Chapman, and that the path forward was to win over their hearts and minds one by one. Suddenly the criticism moved off baseball as an institution, and onto the individual players and managers in the sport. It’s not us, you see, it’s THEM. Those racists lurking out there like Ben Chapman…

But it is no defense of Chapman to say he simply wasn’t all that powerful. His taunts didn’t even work—the Dodgers swept the Phillies, with Robinson scoring the winning run in the first game after a single and a stolen base in the eighth—and he was out of baseball after 1948. Yet Philadelphia didn’t add a Black player until nearly a decade later, so clearly Chapman wasn’t the problem. Of course, the verbal abuse Chapman launched was despicable, and Robinson himself acknowledged the difficulty of playing through it. But he was able to succeed despite it.

Indeed, a common theme of this series was that the main obstacles Black players faced was NOT the racist treatment from fans and teammates—it was the lack of support from their teams. Sam Jethroe was the first Black player in Boston, a city with a notoriously checkered racial history; but he said the fans treated him well, and what really bothered him in later years was that the league denied him a pension after racial barriers kept him from accruing ten years of service time. George Weiss and other Yankee executive insisted that Yankee fans would only accept a certain kind of Black player; but what really held Elston Howard back was not suspicion from fans or teammates, but a refusal of the team to commit to him as a starter. Tom Alston’s mental health challenges were exacerbated not by mistreatment from fans or teammates, but by the Cardinals rushing him to the big leagues so their owner could prevent boycotts from hurting his beer sales.

So figures like Chapman provide convenient scapegoats for the people who actually have power. The presence of some boorish and cruel bigot whose behavior is clearly racist—but is nevertheless not all that powerful or consequential—is used to deflect from the more respected people in power, who carry out racist policies that do far more harm.

This kind of thinking is VERY common today, even (perhaps especially) among people committed to antiracism. Liberals love to insist that racists are secretly everywhere, thwarting any chance at progress. Saying that the country is “racist to its core” sounds radical, but ultimately becomes an excuse for inaction, or unproductive action. Too many people spend their time hunting for proto-Ben Chapmans, trying to out racists one at a time. When people mention that 53% of white women voted for Trump, or dig up old racist tweets to get someone fired, or side with companies spying on their employees, this is what they are doing, whether they realize it or not, and it is ultimately a huge distraction from material change. As the Chapman example shows, identifying and condemning individual bigots and racist behavior isn’t really all that threatening to racist power structures—they’ll put it in a Disney movie or run it on the cover of Sporting News. Systemic change comes from changing systems, not people.