Nobody Wants To Coach Anymore

We’ve reached the end of College Basketball Week here at Undrafted! ICYMI, on Monday we discussed fairness and the NCAA Tournament; Tuesday was about the structural explanation for Antoine Davis’ record chase; on Wednesday, the Lefty Specialists gave their bracket preview; and yesterday, we looked at why NIL hasn’t fixed pay equity. Today we’re talking about the coaching exodus. Thanks for reading, and if you’ve liked it, please consider sharing…

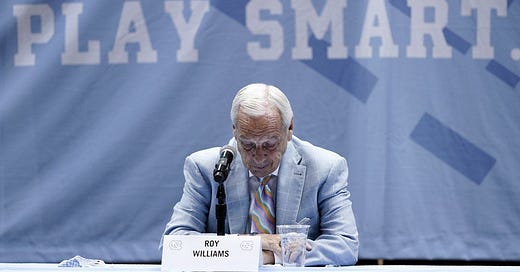

Last week, after being eliminated from the ACC tournament, longtime Syracuse men’s basketball coach Jim Boeheim announced his retirement, after coaching the team for 47 years (although he made a point to say the timing was the school’s decision). This comes the same season that Mike Brey, who has been Notre Dame’s head coach for 23 years, announced that this would be his last season. Last year, of course, men’s college basketball saw both Mike Krzyzskewksi, who had been at Duke for 42 years, and Jay Wright, who had been at Villanova for 21 years, retire. The year before that saw Roy Williams retire after 18 years at North Carolina.

To this list, you can also add John Beilein, who retired in 2019 after 12 years at Michigan and 41 as a college coach; Tubby Smith, who retired in 2022 after 31 seasons as a head coach; and even Bob McKillop, who stepped down as Davidson’s coach after 33 years in 2022. If you add it all up, that means that coaches who have retired in just the last four years had 285 years of Division I head coaching experience, including 6,373 wins, and 12 national championships.

It’s a pretty dramatic exodus, and would seem to require some material explanation.

On one level, this is a pretty recognizable phenomenon: the results of the Baby Boom generation reaching retirement age. All of the aforementioned coaches were born between 1944 and 1961, and all got their start in the profession as the money and attention around college basketball started to explode in the 1970s and ‘80s. It’s hard for modern coaches to match the longevity of people like Kryzskewski and Boeheim in part because it’s hard to imagine anyone building a program from scratch the way those guys did.

But that doesn’t explain why they all seem to be leaving at once. The timing can be explained by several structural changes in the last few years — namely the transfer portal and NIL — which have given more power and agency to the players. The transfer portal makes it much easier for players to leave programs if they are unhappy, and changes to Name Image Likeness rules has allowed players to cash in on their fame, while also allowing schools to lure players from their rivals. Together these changes diminish the power coaches have over their players.

Of course, coaches don’t come out and say that they’re quitting because of the transfer portal or players getting paid. They may even be supportive of those changes. But it has changed the relationship between player and coach in ways that may make the job harder, or at least different. When Roy Williams announced his retirement two years ago, after previously suggesting he would coach as long as he was healthy enough to do so, he said, “I knew that the only thing that would speed that up (was) if I did not feel that I was any longer the right man for the job… I no longer feel that I am the right man for the job.”

“I no longer feel that I am the right man for the job.” That’s about as clear an admission that the game has changed in a way he was not equipped for. Indeed, just a few weeks prior to that announcement, Williams had decried the transfer portal in a conversation with the press:

“I’m old school. I believe if you have a little adversity, you ought to fight through it, and it makes you stronger at the end. I believe when you make a commitment, that commitment should be solid. And it should be to do everything you can to make it work out. We have all, even you guys on this screen here, have seen guys come in as freshmen that were okay or not good. They were better sophomores and they were better juniors and they were better seniors. And they were drafted. So I think it just opens up that there’s no bottom line, there’s no negative. If you don’t like what the coach gave you for pregame meal, you have the right to leave. I’m old school.”

It’s easy to roll your eyes at this insistence that to be “old school” means supporting outdated, exploitative practices. But I like Roy Williams, so I want to give him the benefit of the doubt. After all, it IS true that overcoming adversity is an important thing to learn, and that players can and often do improve over their four years in college. It’s not that Williams is wrong to want college basketball to instill these values.

Of course, where he goes awry is in suggesting that the “old school” system was the right one for doing so. Obviously it’s important to learn to overcome adversity, but it does not follow that we should add unnecessary adversity to people’s lives in order to teach them that. Life will give you your share of adversity to overcome — we don’t need to make it artificially hard to transfer schools on top of that. And it was frankly ridiculous that college athletes faced barriers to transfer that normal college students do not.*

*For all the talk about the transfer portal, roughly half of student-athletes who enter the portal do not even end up transferring. And transferring schools is actually quite common for college students — about ⅓ of them do it at some point. The weird thing was just how difficult it was for college athletes to transfer BEFORE the portal began in 2018.

As for the second part of Williams’ statement, that players can improve over four years, who is to say that an athlete is more likely to improve at the school they’re leaving than the one they’re going to? Indeed, it seems likely that an athlete would transfer from his school precisely BECAUSE he does not feel like he’s improving as much as he should.

Williams’ comments seem to have been inspired by Walker Kessler, a five-star recruit who left North Carolina for Auburn after his freshman season. In his one year at UNC, Kessler played behind Williams’ other bigs — Armando Bacot, Garrison Brooks, and Day’Ron Sharpe — so he never started and played less than 10 minutes per game. Then Kessler went to Auburn, where he started every game, saw his playing time triple, and then got drafted in the first round. Now he is a key contributor to a rebuilding Utah Jazz team that has a shot to make the playoffs.

Is the issue really that Kessler didn’t improve? Or that he didn’t improve on Williams’ timeline? Had Kessler stuck around North Carolina, he’d be finishing his junior season, perfectly positioned to help a Tar Heel team that struggled this year, in part because it lacked size. But since Kessler had enough autonomy to put his own interests ahead of his coach’s, he left.

I don’t say this to pick on Williams. And surely you could find examples of players who transferred and didn’t have the success Kessler did. My point is merely how Williams develops a whole ideology, a whole identity of being “old school,” out of a system he benefited from, without necessarily realizing that’s what is happening. This is why it’s so important to have a materialist analysis of things. I don’t doubt that Williams sincerely believes that it is important to teach kids to overcome adversity. Because it IS important! It’s just kind of convenient that he thinks the best system for doing that is the one where he has all the power…