In case you missed it, we’re celebrating October with Baseball Week this week at Undrafted. On Monday, we had a podcast about the Brooklyn Dodgers. On Tuesday, we had an NLCS preview on Bryce Harper and Manny Machado. On Wednesday, we had an ALCS preview on hating the Astros. And today we’re looking at the scourge of over-managing in October.

October baseball means a lot of things, most of them good: dramatic moments, unlikely heroes, historic upsets. But there are some drawbacks, like too many off days, weird announcing teams, and, worst of all, over-managing.

For most of the season, the in-game strategic decisions a baseball manager makes are not really that important. Of course, a managerial screw up – using the wrong reliever, leaving in a starter too long, not pinch-running when you should have – can cost a team a close game. But close games usually average out over the course of a full season, and no strategic brilliance from a manager is going to make up for the gaps between good players and bad players over 162 games.

But then October comes around, and suddenly the gaps between the teams are smaller and most of the games are closer, and so a manager’s in-game moves suddenly become way more important. There’s probably no way around this, but what makes it worse is that, since managers KNOW their moves are more important — and are going to be scrutinized more closely — they often manage differently. They insert themselves into the game, taking the outcomes out of their players’ hands by issuing more intentional walks, or ordering sacrifice bunts and stolen bases from guys they would never ask to do that during the season. Suddenly the games no longer hinge on the execution of the players, but on the decisions of the managers.

My least favorite example of this, a classic of the over-managing genre, is: Bringing Starters Into the Game in Relief. I absolutely hate this. This happened at least twice in the Division Series round (and then again in last night’s ALCS Game 1) and it backfired each time.

First, and most notably, was in Game 1 of the Seattle/Houston Division Series last Tuesday. The Mariners had gotten out to a couple big leads against the Astros, but then the score was trimmed to 7-5 going into the ninth, when the Astros put two men on with two out. At that point, with Houston’s best hitter Yordan Alvarez coming up, Seattle manager Scott Servais pulled his closer, Paul Sewald, to bring in Robbie Ray. Two pitches later, Alvarez hit a home run to win the game for the Astros. The Mariners were officially eliminated three days later, but it was more or less over with that move.

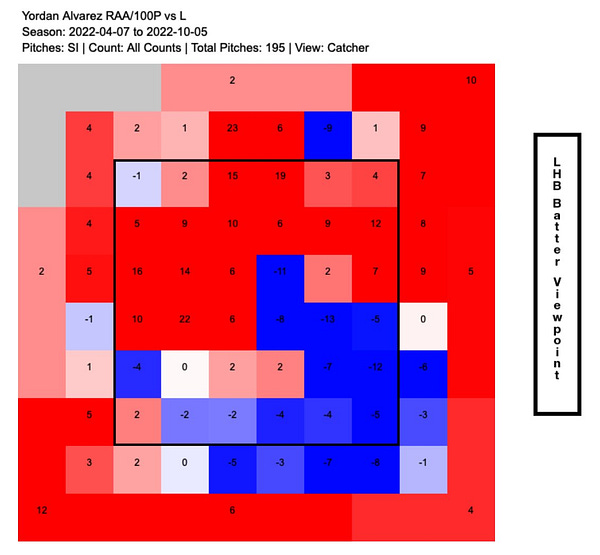

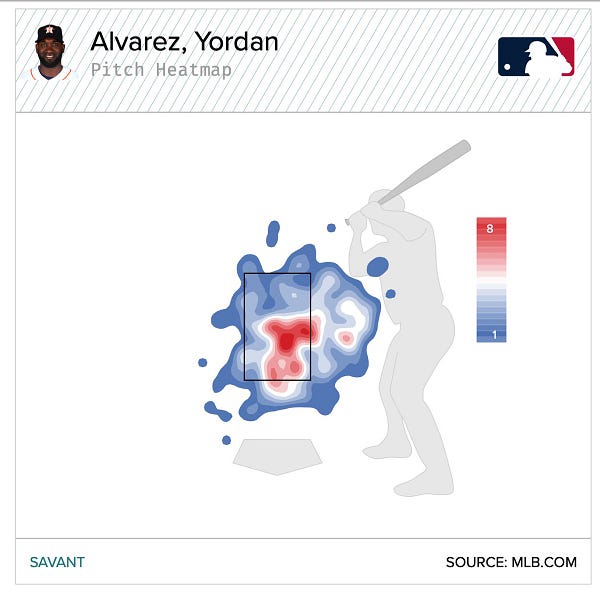

Servais’ logic was obvious: Ray is the reigning AL Cy Young winner! He was the Mariners’ prized free agent signing last year! And he’s a lefty, set to face the left-handed hitting Alvarez! If you want to get more analytical, Alvarez does the least damage against sinking fastballs, which is what Ray was throwing, whereas Sewald throws mostly four-seamers and sliders.

On the other hand, Ray has been so mediocre this season that the Mariners took him out of their playoff rotation. He also gave up the second-most home runs of anyone in the American League, and has the second-highest rate of home runs allowed of anyone on Seattle, and Servais brought him in to face the Astros’ best home run hitter… who then, unsurprisingly, hit a massive home run.

Then, on Friday afternoon, Yankee manager Aaron Boone brought in Jameson Taillon to start the tenth inning against Cleveland. This did not backfire quite so spectacularly – Taillon gave up hits to all three batters he faced, but two were bloop hits, though that proved to be enough for the Guardians to win the game. Again, I can see the logic: The Yankees had already used most of their high-leverage relievers, and they didn’t know how long the game would last, so maybe Taillon can at least give you length.

What bothers me is not that these moves did not “work” (the Yankees especially were doomed more by bad defense than Taillon), or even that the logic behind them is terrible; what really bothers me is the disrespect for labor that these moves show. When a manager brings a starter into a game in relief, he seems to be saying: Anyone can do this. This isn’t a skill that needs to be cultivated. But if baseball has shown anything over the last few years, it’s that relief pitching IS a skill, and not just a refuge for failed starters. Asking pitchers who have never performed this role to suddenly develop that skill shows a disregard for both the pitcher and the job you are asking him to do.

Treating workers with this kind of contempt is normal for management. The role of management is to deskill the workforce on behalf of ownership – to make workers as close to raw materials as possible, so they can be easily replaced and disciplined. But since a baseball team can’t really win without skilled players, a baseball manager can usually only take this so far. During the season, good managers usually understand that their role is to preserve the skills of their players – to prevent injury, to manage workloads, to find the roles where each guy thrives, etc. But then suddenly October rolls around and all that goes out the window.

And, look, I get it. It must be tempting for a manager to believe that pitching is pitching, no matter the inning. But that ignores the different skill sets that are called for in different situations. Part of the reason Robbie Ray is among the league leaders in home runs allowed is that a starter rarely costs his team the game by giving up one home run – if you’re starting, then your offense always has a chance to catch up. A starting pitcher can be reasonably effective while still giving up a lot of home runs. But relievers, who are used to pitching in higher leverage situations, have to be more careful about surrendering the longball.

Similarly, a starter who is trying to go through a lineup multiple times might pitch to contact to avoid running up his pitch count. But if you’re pitching in the 10th inning and the go-ahead run is on third base with nobody out – as was the situation Taiilon faced against the Guardians – then you might want a pitcher who can dial it up for a strikeout on command.

Obviously I’m not saying that no starting pitcher is capable of pitching out of the bullpen. Some of the biggest playoff moments involve aces like Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, and Mike Mussina coming into big games and locking down the middle or late innings. But Johnson, Martinez, and Mussina are all Hall of Famers – their ability to adapt is part of what made them all-time greats. Taillon and Ray (and Frankie Montas, who Aaron Boone called on last night) couldn’t even make their teams’ division series rotations. More to the point: Relief pitching has gotten a lot better since the early aughts, and both the Mariners and Yankees had options in their bullpen who were at least as good as the starters, and more used to pitching in those situations. So why didn’t those managers make the more obvious, more traditional moves to guys who were used to those situations?

Part of me thinks that the real reason managers make these moves is that they are enamored with the idea of making a “gutsy” October call that they would never make in the regular season. They remember Johnson and Pedro coming into those games, and they’re trying to replicate those moments. The fact that the call is questionable is what makes it good, since it underscores how important the game is.

But this is the exact trap that management falls into all the time: Thinking that they know best, that their strategies or clever gambits or big-picture philosophies are more important than the skills and expertise of the workers. Pitchers are workers who have honed and cultivated their craft – they are not buttons to be pressed at the whim of a manager. When socialists or Marxists talk about “the alienation of labor,” this is basically what they are talking about: Workers, who usually know their jobs and their capabilities better than anyone, being told what to do and how to do it by bosses who view them as interchangeable parts.

The thing that makes sports great, though, is how often it exposes this bullshit for what it is. Because in sports, the players are the ones who win. No matter what strategic moves your coach or manager makes, it’s the players on the field or court who have to execute. The coaches and managers are there to help the players, not the other way around, and the good ones usually know that.