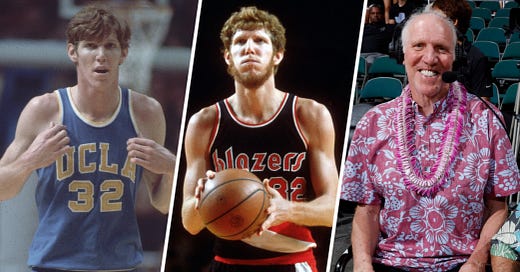

RIP Bill Walton, 1952-2024

Quick programming note: I meant to have Part Two of the superteams piece I began last week ready for this week, but with Bill Walton passing away this week, I wanted to address that first. So Part Two will be delayed, probably until next week.

Since I was too young to see him play, I’ll always think of Bill Walton first as an announcer. There was nobody who called a game like him, whether he was comparing Boris Diaw to Beethoven in the Age of Romantics, talking shit about Liberty University, or going over the history of California’s bear population — and, of course, doing all these things while the game was going on.

One night a couple years ago, I turned on the final few minutes of a Pac-12 game. UCLA was leading Arizona by just six points, and Oumar Ballo was at the free throw line for the Wildcats… but Bill Walton was talking about the Canary Islands for some mysterious reason. He turned to his play-by-play guy Dave Pasch (who called so many games with Bill and had a great rapport with him) and started to ask, “Did you ever read the book…” but then the crowd got really quiet for the free throws. So Walton starts whispering, “...about…” but of course Pasch, realizing now that it’s a close game in the final minutes, tries to bring Bill’s attention back to the court: “We'll hold off on any book recommendations until the postgame, especially if it’s about eels again” (suggesting, of course, that at an earlier point in the game Walton made ANOTHER book recommendation, apparently about eels). But Bill was determined to finish, bellowing, “No, it was about surfing in the Canary Islands!”

Bill Walton just had such a wide range of interests, and so much enthusiasm about all of them, that listening to him was a unique experience. And so there’s been so much said about Walton this week, since there is so much to say about his life, from his love of the Grateful Dead to his political activism to his relationship with John Wooden. I’m not sure what I can possibly add, but I wanted to say a few words about Walton's playing career.

Walton liked to refer to himself as “the luckiest guy in the world” and that was the name of the 30 for 30 about his life:

The irony, of course, was that he was plagued by bad luck as a player, dealing with brutal injuries for more or less his entire career, going all the way back to high school. He managed to put together an amazing career at UCLA, probably the best college basketball career ever, but he missed big chunks of both his first two pro seasons with injuries. In his first healthy season with the Portland Trail Blazers, the team won the Finals. The next year they got off to an amazing start, winning 50 of their first 60 games, and seemed like a budding dynasty. But then Walton got hurt again. (He still won the MVP, despite missing 24 games.) He tried to play in the playoffs, but only aggravated his broken ankle. He never played for the Trail Blazers again.

Then he went to San Diego, where injuries kept him out of more games than he played — he played in over half his team’s games just once in six years with the Clippers. (About his time with the Clippers, Walton would say: “The checks bounced higher than the basketballs when Donald Sterling took over. The basketball was awful, and the business side was immoral, dishonest, corrupt, and illegal. Other than that, it was all fine.”)

Luckily, he was able to stay healthy for one great season as Boston’s sixth man for the 1985-86 Celtics — the best Celtics team of that decade. So he won two championships, but he played in fewer than 500 NBA games, starting only 117 because of injury. (For comparison’s sake, LeBron James started more games before he turned 20 years old.)

Some of this was bad luck: Walton was born with congenital birth defects in his feet that made it nearly impossible to stay healthy. And some of it was mistreatment: The Trail Blazers’ medical staff misdiagnosed (or lied about) a broken ankle to rush him back for the playoffs. But obviously none of it was his fault, and Walton would have every right to feel bitter or angry about how his career unfolded and all his bad luck. But that just wasn’t who he was — he was the luckiest guy in the world.

Much has been made of Walton’s leftist politics and activism on matters from environmentalism to anti-war advocacy. And while I obviously love that stuff, I am hesitant to define Walton by it, in part because his politics got iffy by the end, and in part because I think it’s important to remember that you can be a good person with bad politics (and vice versa).

But I’m not sure you can be a good person without a healthy respect for luck. By recognizing the role that luck plays in all our lives, you develop an appreciation for what life gives you and a charitable attitude towards others. It is only when you liberate yourself from this rigidly individualistic false consciousness that capitalism often imposes on you — that you are responsible for all that happens to you, and if you are suffering it is because you deserve it — that you can be truly moral, and truly happy.

This doesn’t mean you let people off the hook for their actions, or embrace nihilism. Bill Walton never stopped taking stances, or making fun of Liberty, and his life is proof that you can have a healthy respect for how material conditions shape our lives and also have a happy, enthusiastic, loving attitude towards everyone around you.