“I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.” —Stephen Jay Gould, scientist/socialist

“These men couldn’t do what I did because they didn’t have the chance. But they dreamed the dreams I did when they were 15, too. And they taught me and they gave me the combat training so that I could do it.” —Willie Mays, on his Negro League teammates

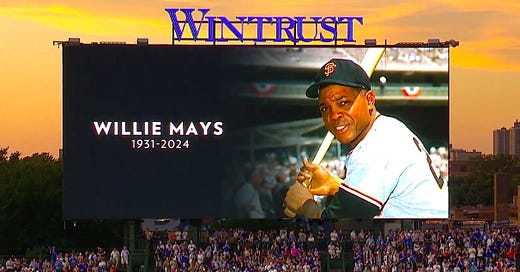

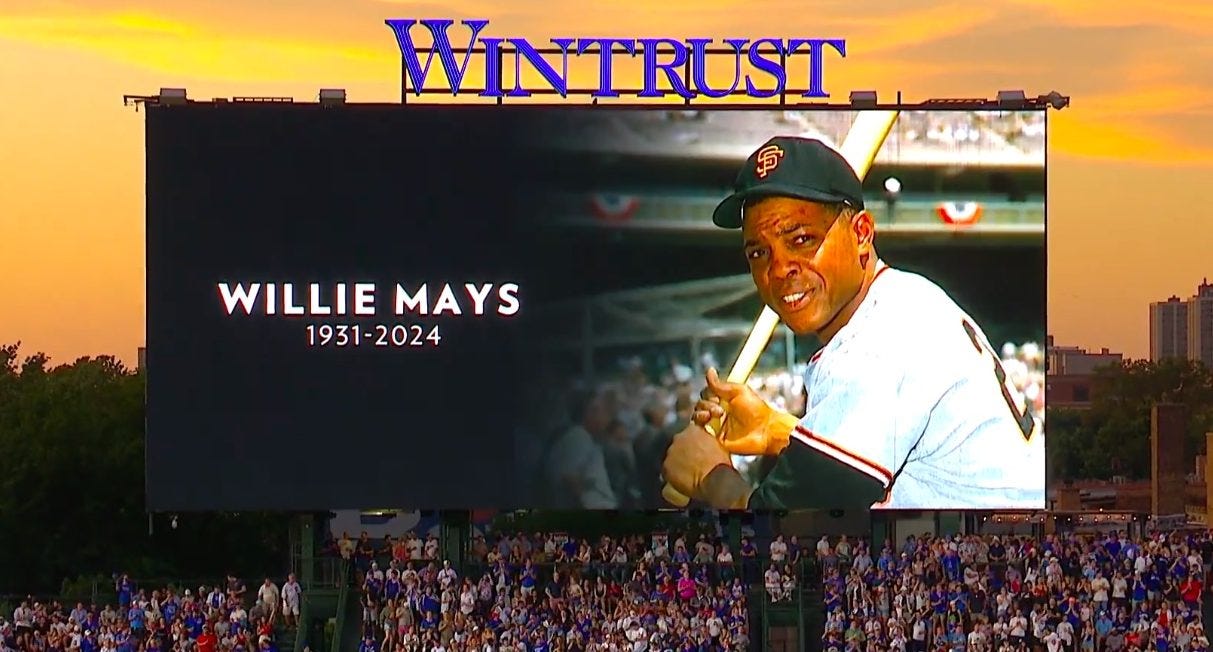

What is even left to be said about Willie Mays, the greatest player who ever lived?

I’m not sure, but let’s start with Artie Wilson. You probably haven’t heard of Wilson, but he and Willie Mays had a lot in common: Both were born in Alabama. Both made their professional baseball debuts with the Birmingham Black Barons. Both spent most of their baseball careers on the West Coast, and settled there after their playing careers were over. And both made their MLB debuts with the New York Giants in 1951.

For Artie Wilson, it had been a long and roundabout path. After he won the 1948 batting title in the Negro American League, both the Yankees and the Indians tried to purchase Wilson’s contract from the Black Barons. The league ruled that Wilson belonged to the Yankees, but Wilson himself wanted to play for Cleveland and didn’t accept the ruling. And for good reason: The Yankees, who wouldn’t integrate their Major League roster for another seven years, seemed to have no real interest in Wilson, only pursuing him to keep him away from Cleveland. They tried to send him to Newark and offered him a lower salary than he had been making in Birmingham.

So instead Artie Wilson went to the Pacific Coast League, where he played most of the next two seasons with the Oakland Oaks. Then, in 1951, he was sent to the Giants, where he impressed manager Leo Durocher and made the team out of spring training. He and Ray Noble joined Hank Thompson and Monte Irvin, who had first integrated the Giants back in 1949, giving New York four of the first 15 Black players in baseball.

But Wilson didn’t play much. Blocked at every infield position by more established players, Wilson was limited to a reserve role for that first month, and got only four hits in 22 at-bats. In the meantime, Willie Mays had been hitting .477 with 8 home runs in Triple A, and the team decided it was time to call up the 20-year-old phenom.

There was no official rule that Mays had to replace another Black player, but everyone expected that he would. Irvin would later mention “an unwritten quota system at the time that limited the number of black players on a ballclub.” Teams also preferred to have an even number of Black players, so they could room together on the road. Thompson and Irvin were by then established parts of the Giants’ lineup (Irvin led the team in Wins Above Replacement that season), and Noble, as a catcher, played a more important position.

So Wilson was the odd one out. He was sent down to make room for Mays on the Giants, and never played in the majors again. Wilson went back to the Pacific Coast League, where he won three more batting titles. And Mays, of course, became Willie Mays.

To be clear, I am not trying to suggest that Wilson could have ever been Willie Mays. Mays was singular. Mays was special. He was the greatest to ever do it. And Wilson was just a pretty good singles hitter. But I would suggest the difference between them is smaller than anyone usually cares to admit, and when I think about Mays, I can’t help but think about other What-Could-Have-Beens…

Part of the reason so many people think Willie Mays was the greatest player who ever lived is how his career excites the imagination. Of course, Mays has big numbers that are real and tangible: 660 home runs, 3,293 hits, 156.2 Wins Above Replacement. And he also has iconic moments that every fan is familiar with. When you think about Willie Mays, you picture that grainy footage of him running the bases, or black-and-white movies of him playing stickball with kids, or that clip of The Catch everyone has seen:

But what really works to Mays’ advantage is the way all this paints a portrait of Mays as a player, while ALSO leaving that portrait about 10% incomplete. We have footage of him playing, but not the extensive, surveillance-level footage we have of modern players; it’s all grainy and hazy (the camera angles on The Catch are legendary for how incomplete they are). We have his career stats, but he missed nearly two years because of military service, so it’s fair to wonder what his home run and hit totals COULD have been.

In other words, everything about Mays’ legacy allows fans to fill in the detail with their own imaginative flourish. And how can anyone compete with a fan’s imagination? Crucially, though, Mays was real to fans in a way that earlier Greatest Ever candidates couldn’t be: Babe Ruth never played on TV, Ty Cobb’s stats come mostly from the Dead Ball era; etc.

But was Willie Mays REALLY the best player ever? Buck O’Neil, who lived 95 years, always said that Mays was the greatest Major Leaguer he ever saw. But the greatest PLAYER he ever saw was Oscar Charleston. As Buck once told Mays, “He was you before you.”

Charleston, who was overlooked for much of baseball’s history, has gotten a lot more attention in recent years. In 2020, when Joe Posnanski published his list of the Top 100 players of all-time, he put Charleston at #5. In 2022, Bradford Doolittle at ESPN wrote a piece asking whether Charleston was the greatest player ever.

The frustrating thing about these pieces, though, is that they all have to end inconclusively, since we have so little information about his playing career. Unlike Mays, there’s no extant footage of Charleston playing, and the records of the Negro leagues are incomplete. He was not the Paul Bunyan-esque figure that Satchel Paige was, so his legend could not be effectively passed down through oral history. Nor do we have the gaudy statistics for him we have for other Negro league greats — when MLB added Negro league stats to their official leaderboards last month, it was Josh Gibson, not Charleston, who vaunted to the top of several major categories.

For Charleston, what we mostly have is dozens of contemporaries — from Buck O’Neil to Honus Wagner to Turkey Stearnes to John McGraw — who all called him the best player they ever saw. He was compared to Mays because they both seemed to have a supernatural command of the game that went beyond mere numbers. And to modern fans, Charleston is only supernatural, a pure ghost; he cannot be made real in the way that Willie Mays can.

Of course, the point of debating the Greatest Baseball Player Ever is not really to come up with an answer. The point is to highlight how exceptional someone like Willie Mays really was — “exceptional” in a very literal sense.

If you are reading this, then odds are you never saw Willie Mays play. I certainly never did. I learned about him from stories. And what those stories always emphasized is how unique he was a player: Nobody played centerfield like him. Nobody ran the bases like him. Nobody understood the game like him. Nobody brought as much joy to the game as he did. He was the exception to all the rules that usually bound other players, the mere mortals on the diamond.

Obviously it is a testament to Mays’ character and talent that he was able to defy those rules. But it ought to take nothing away from Mays as an individual to say that, often, an exception like him is not actually the result of some unique greatness; it is often the result of realizing that the rules holding so many others back — others like Artie Wilson and Oscar Charleston — are not laws of nature, but man-made rules we are all too content to accept despite the way they hold so many people back. And it is worth wondering what other rules like that are currently in place…