“Sabermetrics” Was Always Just Wage Suppression

Last week, over at his Substack, Freddie deBoer wrote a piece provocatively titled “Yes, Sabermetrics Ruined Baseball.” Seeing the headline, I was pretty excited—it’s always great to have more socialists in the sports takes game. And sabermetrics provide ample fodder for deBoer’s distinctive scorn. But the piece turns out to be mostly predictable complaints about the state of the game today: Games are too long; there aren’t enough balls in play; the obsession with launch angle has gone too far; etc. All of this is true, as far as it goes, but almost any baseball fan will tell you the same thing. It’s a surprisingly conventional list of complaints for deBoer; what’s missing from it is the real role that “sabermetrics” has played in all of this.

If you say “sabermetrics” or “analytics” to any baseball fan, you will likely get one of three reactions. The first, from the more traditionalist fans, is to gnash their teeth or yell angrily at the sky about how the numbers have ruined the game. There aren’t as many of these people as there used to be, but they’re still out there (a lot of them are announcers for national broadcasting teams)—and, honestly, I increasingly find myself agreeing with them, for reasons deBoer outlines.

The second reaction is from younger fans, or more empirically minded fans, who like analytics and roll their eyes at the first group. And the third reaction, from those closest to the game, is think even using words like “sabermetrics” and “analytics” is quaint—at this point those things just are baseball. The battles that started decades ago are long over. There are no more Art Howes or Mike Scioscas, insisting on managing from their gut. Even Tony La Russa has come around. We used to have debates about sacrifice bunts and stolen bases—but nobody does those things anymore, so those debates are purely academic now. Sabermetrics won so decisively that most people missed what the fight was even about.

Most people think the debate was about numbers, or math, or technology, and there’s certainly something to that. Statistics like WAR and FIP have gone mainstream, and those rely on some complicated calculations. Other stats, like PITCHf/x data and Statcast numbers, rely on technology that wasn’t in place just a decade ago. It doesn’t help that “sabermetrics” sounds kind of like “cybermetrics,” which makes it sound like some kind of futuristic term. (It’s really just a pronunciation of the SABR acronym for the Society for American Baseball Research, of which many early advocates for these numbers were members, but which does tons of more qualitative research as well.)

But if you go back and read Michael Lewis’ Moneyball, which really brought these debates into the mainstream, his main concern was how low-payroll teams could compete against high-payroll teams. His focus was not really the weird stats themselves, but the fact that those metrics were underpriced in the free agent marketplace, which allowed a team like Oakland (who had a $40 million payroll in 2002, which was 28th in the league) to compete with a team like the Yankees (whose league-leading payroll in 2002 was $125 million). In other words, the main conflict was about how to win while paying players less.

The irony, supposedly, is that once Lewis’ book became so popular, the market inefficiencies Billy Beane, Oakland’s GM, was exploiting no longer existed. So teams had to find NEW inefficiencies, whether that meant using WAR or FIP or wRC or exit velo or some new proprietary data that isn’t even made public anymore. But the essence of the issue is the same: How can we find guys who are good, but who nobody else realizes are good, so that we don’t have to pay them like “good players”?

And, truthfully, the role of advanced stats in solving this was always overblown. Billy Beane did not field successful A’s teams because he found a bunch of diamond-in-the-rough free agents with high wOBAs—he did it because he had three elite starting pitchers and a bunch of other great players who had not yet reached free agency. And how did he get those guys? Well, Oakland did not have a winning season from 1993 to 1998, so they had a bunch of high draft picks, some of which were used on guys like Mark Mulder, Barry Zito, and Eric Chavez.

In other words, the A’s did it by tanking. In fairness, I think they tanked accidentally, but ultimately their model was not much different than the model used by the Royals to win in 2015, the Cubs to win in 2016, the Astros to win in 2017, and now being attempted by about one third of the league. The irony is that Lewis celebrated the A’s for achieving a kind of parity with the higher payroll teams, but their legacy is the main reason the league is now so imbalanced—with so many teams tanking, baseball has seen a sharp rise in the number of 100-win and 100-loss teams.

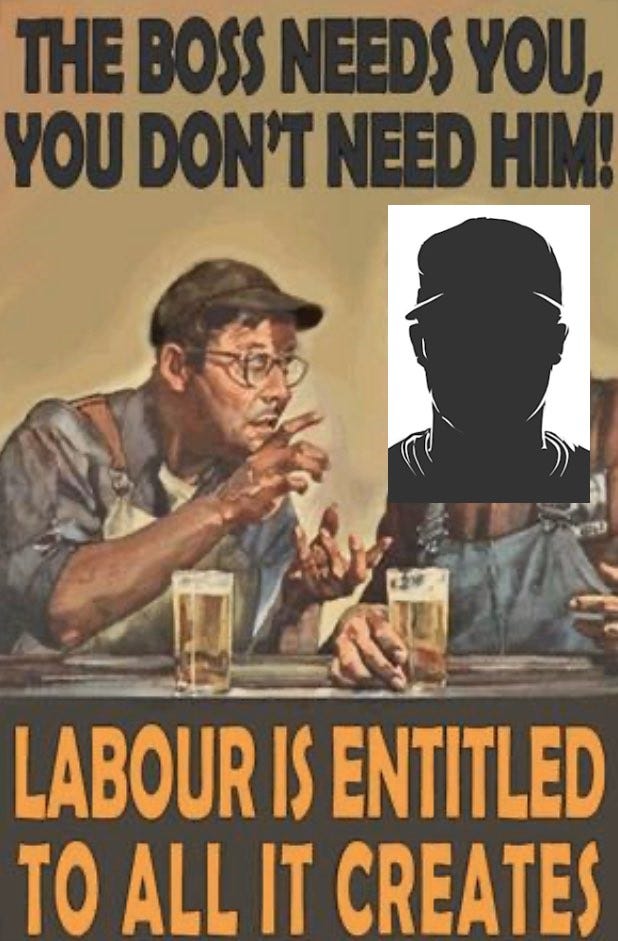

Ultimately, the sabermetric revolution was about getting fans to identify with GMs and find some kind of value in the ability to maximize the number of wins per dollar spent, as opposed to just maximizing the number of wins. That’s why now even big market teams like the Cubs and Astros and Red Sox tank and trade away iconic players like Kris Bryant and Mookie Betts. The goal is always to keep payroll down.

And it’s how sabermetrics “ruined” baseball. The numbers are really not the problem—I like the numbers! The problem is that now sabermetrics means things like using openers in playoff games, or shifting on every batter, or bringing relief pitchers into games in the fifth inning, or grooming a second baseman to hit .190 with 28 home runs. Is any of this stuff good for helping teams win games? Eh, maybe, a little bit (the evidence is actually surprisingly thin for a lot of this stuff).

But it’s DEFINITELY good for keeping salaries down. It’s much easier to avoid paying a starting pitcher like an elite starter if you never let him face more than 18 batters in a playoff game (pour one out for Blake Snell again). It’s much harder for a guy’s defense to get appreciated (and properly compensated) if he’s always playing in a shift. It sometimes seems like baseball is just a few years away from turning players into total commodities—everyone will be off the rack, either a relief pitcher who can throw 102-mph for two innings every three days, or a positionless fielder who will stand wherever on the field you tell him to while reliably going 1-4 with a home run and three strikeouts. Owners can just pay all these guys the minimum and we’ll never have to learn their names. A true victory for the data guys…