If you have been paying any attention to this NFL offseason, then you have likely encountered some discussion of the Running Back Problem. Holdouts by two of the league’s premiere running backs, Saquon Barkley and Josh Jacobs, raised the issue of running back pay, which has been lurking in the background for years as football becomes more pass-focused and teams shift to running back tandems instead of relying on one primary ball-carrier. (Even OJ Simpson has weighed in…)

Last month, though, Domonique Foxworth, the former NFL cornerback, NFLPA president, and current ESPN personality, offered an interesting suggestion for how to solve this problem: using the Performance-Based Pay Pool to supplement the salaries of running backs.

To be honest, I didn’t even know the Performance-Based Pay Pool was a thing that existed, but last season it paid out $336 million. The way it works is a little complicated, but it’s basically a way to distribute money to guys who played more than they were expected to. That usually means guys on minimum or near-minimum deals who ended up starting, or playing a significant number of snaps for their team.

This seems like a great idea. Normally, the amount someone is paid is based on what they are expected to contribute, since a salary is generally negotiated in advance of doing the job. But the PBP Pool pays people based on what they actually did. It is, by necessity, a little crude, since comparing the production of different players at different positions and on different teams is challenging: For example, the PBP Pool is based entirely on snaps played. But this is still an objective, empirical metric, which is always better than the whims and judgment of your employer.

Anyone interested in paying people fairly should be excited about things like the PBP Pool. The more that compensation decisions get shifted away from a priori negotiations with employers and towards empirical measures of production, the better. In an ideal world, you’d never have to negotiate pay with your boss ever again.

There are many problems with negotiating your pay directly with your employer, many of which are well-known: discrimination, favoritism, power-imbalance, etc. But these are usually seen as part of some other problem, whether racism or misogyny or whatever, and not as something inherent to capitalism itself. So we try to fix them whack-a-mole style, with a bunch of ad hoc reforms to the process. Ban discriminatory hiring! Let people sue for pay disparity! Encourage people to discuss their salaries with coworkers!

But the basic problem is more fundamental. The real problem is that employers always want to suppress an employee’s pay because, if they do, they keep the money. Under a capitalist system, where firms are privately owned, then the revenue generated by the firm belongs to the owner, not the worker who produced the value. So obviously they will try to suppress salaries in any way they can. Of course they will have an easier time doing this against more vulnerable people, people who are the victims of racism or misogyny or homophobia or what have you, but the central problem here is a problem of capitalism.

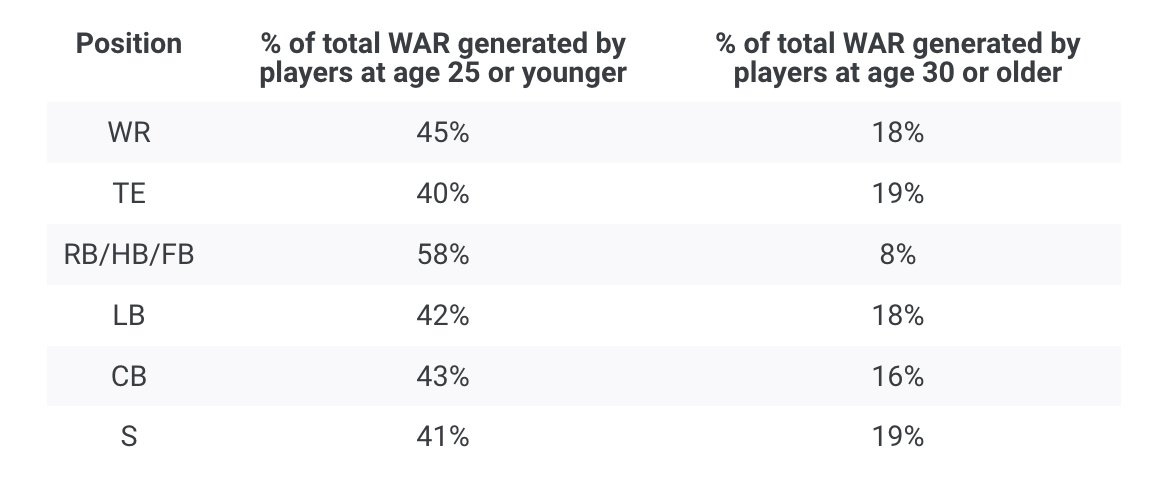

After all, the Running Back Problem isn’t the result of some larger cultural force. It’s just a quirk of the salary cap structure: Because of the physical toll that being a running back takes on the body, they have shorter careers than other positions, and so most of their production tends to come before they reach free agency. Look at this comparison of running backs to other positions:

So when teams have a chance to bid for free agents, it rarely makes sense for them to bid on running backs. That money could be better spent on players whose contributions are ahead of them, rather than behind them. After all, when teams do sign running backs to long-term deals, they usually come to regret it: The Cowboys’ big contract with Ezekiel Elliot is now seen as a cautionary tale.

Ironically, this is not something that is easy for a union to address. After all, the money teams save by not paying running backs generally goes to other players; any solution that specifically seeks to boost running back pay, without also increasing players’ share of the revenue, is going to come at the expense of other players in the union.

This is why strong unions, while certainly necessary for fair pay, are not enough. You actually need to challenge the owner’s right to surplus revenue generated by the players. In other words, you need socialism. But this need not be as radical as it sounds — the Performance-Based Pay Pool shows us a way!

I’m not sure how feasible it is to use this existing Pool to make up for the pay disparity among running backs. The most money the Pool paid to a single player in 2022 was $880,384 that went to Eagles safety Marcus Epps; that roughly doubled his salary, but Barkley and Jacobs each make more than 10x that amount, and were holding out over differences of over $1 million per season. You don’t have to be a math whiz to realize that, in order to use the PBP Pool to meaningfully address the Running Back Problem, you’d either have to pay fewer players from the Pool, pay those players less, or significantly increase the size of the Pool. Any one of those options is going to require a pretty difficult negotiation.

But a pool like this one, whose size was determined by the league’s revenue and whose output went to players based on some objective measure of their contributions, would not only fix the fair pay problem, but would also eliminate the contentious negotiations between player and team. Just shrink the owner’s role until there’s nothing left for him to do, and all your problems will be gone forever…