With news of Tom Brady’s (likely? possible? not actual?) retirement breaking yesterday, we are likely to see an onslaught of odes to the NFL’s GOAT. You might expect Undrafted to have a contrarian take, but I stopped pretending that Brady wasn’t the best long ago. This newsletter is pro-Tom Brady:

But I wanted to use Brady’s retirement as an occasion to illustrate the tensions between individual and collective success. One problem with GOAT debates is that, in team sports, it can be hard to isolate an individual’s role in the overall team’s success. This problem is particularly acute in football, because of the outsized role played by quarterbacks. Quarterbacks are so important, particularly to the modern game, that it can be tempting to attribute any team success to his performance, and blame him for any of his team’s failings.

Some of this is legitimate, but a lot of it is the result of a common temptation to assign collective triumphs and failures to a single individual. The civil rights movement is credited to Martin Luther King; D-Day is credited to Dwight Eisenhower; the iPhone is credited to Steve Jobs. In reality, all these things are obviously the cumulative result of the work of many people whose names we never know. But we can’t help but elevate individuals above the collective.

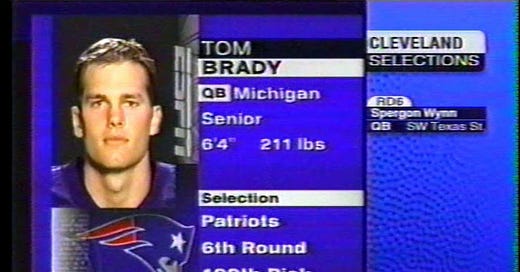

And Tom Brady was, at one point, a major beneficiary of this temptation. In the early days of the Patriots dynasty, Brady was the face of the franchise, even though he was seen by some as a “system quarterback.” This was really just a fancy way of saying that the team was not built around Brady. From 2001-04, the Patriots’ success was really built around their defense, which generally finished among the best in the league. The one year in that stretch it didn’t—2002—the Patriots missed the playoffs.

Even the offense was not built around Brady. In those years, the Patriots ran the ball almost as often as they threw it, if not more. The one year they did build their offense around Brady’s arm was, again, 2002, when they missed the playoffs. Meanwhile, in Indianapolis, Peyton Manning was throwing the ball more often, for more touchdowns, and with a higher completion percentage. Manning even set the record for single-season touchdown passes in 2004.

Still, Brady’s teams were more successful, and Brady was the face of that success. He was the quarterback; he was handsome; he shined in the playoffs. In many ways, Brady in this period was like Troy Aikman in the early 1990s: He did exactly what was asked of him in the regular season; he shined in the playoffs; he rode the team’s defense and running game to three Super Bowls in four years.

At that time, the argument for Brady’s individual skill relied on vague statements like “He knows how to win.” It was mostly bullshit. But then a funny thing happened: The Patriots’ identity changed. In 2007, they had the undefeated regular season based largely on their offense, and Brady broke Manning’s touchdown record. But even accounting for that outlier of a season, the team’s evolution was consistent: Their defense got worse, and their offense got better and more pass-heavy. In 2011, the Patriots’ defense was 31st in yards allowed and 15th in points, but New England still made the Super Bowl because Brady had one of his best seasons ever: He threw for 5,235 yards and 39 touchdowns. His passer rating for the year was 105.6. Perhaps more importantly, the Patriots threw the ball almost 40% more than they ran it. The offense carried the team, and Brady was the offense.

For this period, Brady basically became a better version of Peyton Manning. Compare their respective averages from two five-year stretches:

1) 37 touchdowns; 9 interceptions; 4,633 passing yards

2) 39 touchdowns; 12 interceptions; 4,560 passing yards

The first is Tom Brady’s average numbers for the five seasons he was healthy between 2007 and 2012. The second is the average numbers from the five seasons when Peyton Manning won the MVP award, including two different times he set the record for passing touchdowns in a season! In other words, Brady went from replicating Troy Aikman’s peak (but probably slightly better), to replicating Peyton Manning’s peak (but probably slightly better).

It’s not just that Brady was finally able to put up big passing numbers. It’s that he showed a rare ability to adapt to what his team needed. The NFL’s history is full of great quarterbacks, including Aikman and Manning, but what makes Brady special is that he managed to be two different types of elite quarterback. In the early 2000s, when teams still succeeded by running the ball and playing defense, Brady was the perfect quarterback for that system. Then, as the game evolved and throwing for 4,000 yards per season went from being elite (before Brady came into the league in 2000, only five quarterbacks in NFL history had multiple years of at least 4,000 passing yards) to almost standard (in 2021, ten different players did it), Brady dominated at that too.

And he wasn’t even done. In 2011, Aaron Rodgers started combining prolific passing with unprecedented accuracy. Before Rodgers, it did not seem possible to throw for at least 4,000 yards and 30 touchdowns, without throwing at least 10 interceptions. Brady, Manning, and Brett Favre had each had single seasons like that, but nobody seemed able to do it consistently. But between 2011 and 2016, Rodgers did it four different times.

So then Brady started doing it too. He reached that milestone in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2018 (and probably would have done it in 2016 if he hadn’t been suspended for Deflategate). The Patriots reached the AFC Championship every single year in that stretch, and won three more Super Bowls. Somehow, Brady managed to stitch together the peaks of Troy Aikman, Peyton Manning, and Aaron Rodgers—three of the greatest quarterbacks of all-time.

But obviously Brady’s greatness is not about individual success or statistics. It’s pretty easy to imagine, with the way the NFL is trending, all of Brady’s career passing records getting broken by someone like Patrick Mahomes or Joe Burrow. But it’s harder to see someone matching his seven Super Bowls, and this is where Brady becomes a true working class icon.

When people say things like “Tom Brady knows how to win,” it’s usually just some bullshit to ascribe team accomplishments to an individual. A more accurate statement would be: “Tom Brady keeps learning new ways to win.” He is not LEADING his team to victory, he is subordinating himself to the team in order achieve victory. He evolved with his team and the league, putting aside his ego and becoming whatever kind of quarterback he needed to be to win. When winning meant being a system quarterback, he did that. When winning meant setting the record for passing touchdowns, he did that. When winning meant cutting his interceptions while still throwing as many touchdowns, he did that, too. It is hard enough to be elite at winning one kind of way. It’s almost unprecedented to be elite at ALL OF THEM.

That’s what makes Brady the greatest player ever, that ability and willingness to become whatever his team needs. There is something beautiful about the way Brady has managed to make his individual success always aligned with his team’s. It’s true solidarity. I used to think it was a mark against him that Brady’s first five Super Bowl wins all came down to the last play; it made them seem almost fluke-y. But now I think that is the perfect embodiment of Brady’s skill. He will do everything necessary for the team to win, and not a single thing more. Anything extra is just you trying to impress the boss…