As we approach baseball’s All-Star Break, one of the big storylines to emerge in the 2023 season has been the relative disappointment of teams with big payrolls. Perennial big spenders like the Dodgers and Yankees are not in first place, chasing teams spending half as much (Arizona) or even less (Baltimore, Tampa Bay). Philadelphia (4th in payroll) is behind Miami (21st) in the standings. And Toronto (7th) would be out of the playoffs completely if the season ended today.

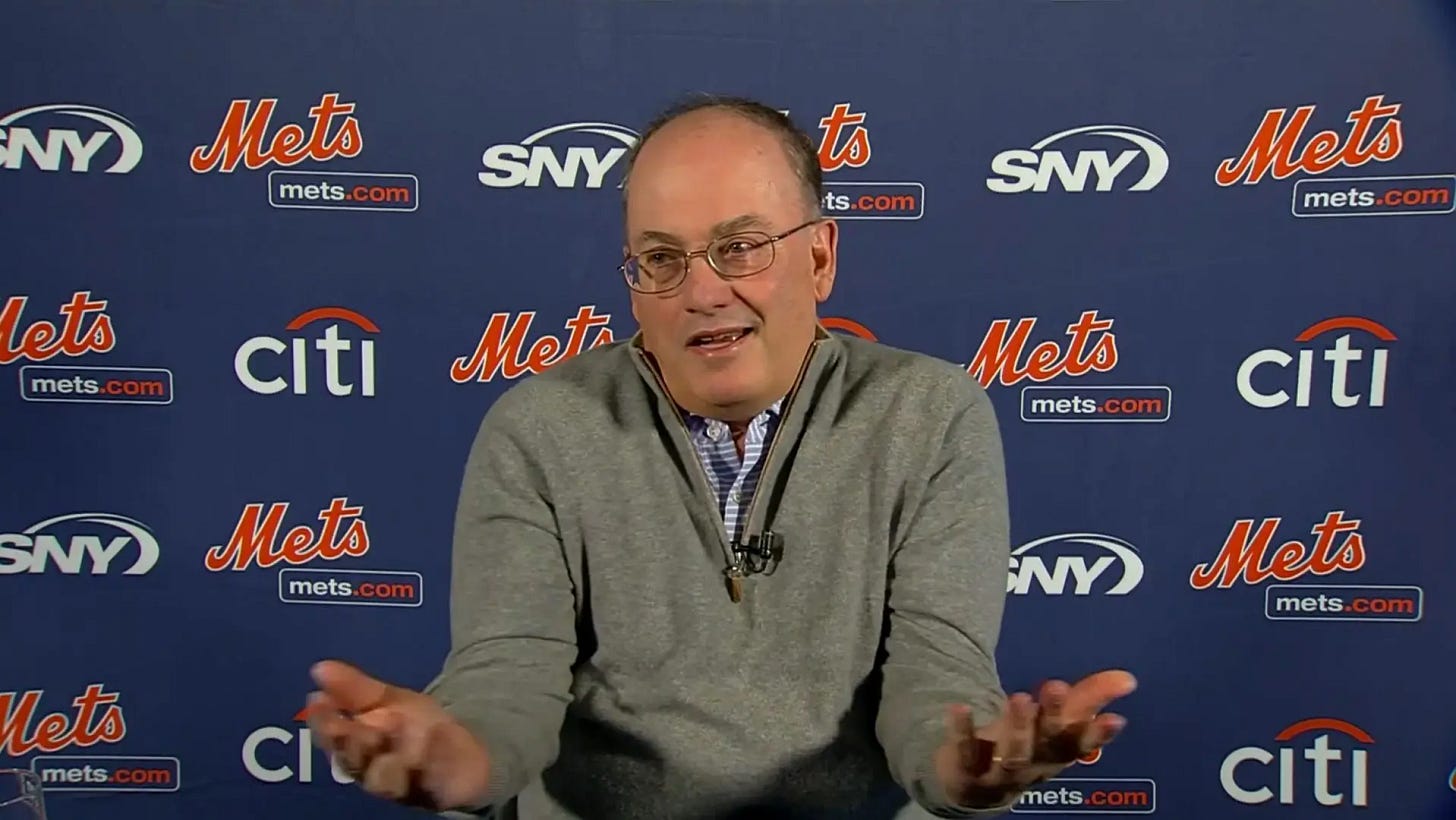

But most disappointing of all are the New York Mets and the San Diego Padres, who are respectively 1st and 3rd in the league in payroll, yet neither is close to a spot in the postseason. They are five and seven games below .500 respectively, and at least six games back of the last wild card spot in the National League. As the trade deadline approaches, both teams look to be sellers, likely to focus on 2024 instead of this season. For the Mets in particular, who came into the season with the highest payroll in MLB history, it is a huge letdown.

And it has set off another round of debate about whether spending money is actually the best way to win in baseball. This idiotic debate surfaces practically every season, whenever a team with a relatively high payroll disappoints, or a team with a relatively low payroll does well — which, given the way baseball works, happens fairly often. So let’s do a quick rundown of the relationship between winning and money in baseball, to put these debates to rest.

In Major League Baseball, there is a clear correlation between spending money and winning championships or making the playoffs. Nearly every championship team since the Wild Card era began has been in the top half of the league in payroll, as have 65% of playoff teams over the last five non-Covid seasons.

Nevertheless, that’s not a very STRONG correlation. Over the last 15 years, championship teams are as likely to come from the middle of the pack payroll-wise (10th thru 15th) as they are to come from the top five. There are also teams that have been able to consistently field playoff teams (Tampa Bay, Minnesota, Cleveland) without ever being among the league’s top spenders.

Putting these facts together is obviously more nuanced than your standard takes about “Teams just buy championships!” or “Spending money on free agents is a waste!” The truth is that you CAN be competitive without spending money on free agents, but it is harder and it’s nearly impossible to win it all that way. Even a core built through drafting and development typically needs to be supplemented with players signed in free agency.

The quirkiness of all this stems from the peculiar nature of baseball’s collective bargaining agreement. Major League Baseball grants an unusually long period of team control for young players: generally six years, as opposed to ~4 in the NBA/NFL, and three or less in the NHL. When you combine this with baseball’s longer development time, the result is that players often play their entire prime before they ever reach free agency. Baseball also does not have a salary floor or a specific percentage of the revenue that is allocated for players. Thus teams that do not want to spend money don’t have to, and so there is a much bigger spread between rich teams and poor teams.

Baseball’s salary structure therefore makes it possible, in theory, to field a good team full of great players in their prime without signing a single free agent. In practice, though, it isn’t so simple. Players get hurt, prospects don’t pan out, etc. In order to compete with any kind of consistency, you need to be willing to add veterans, some of whom are pricey.

The low payroll teams that DO compete are only able to do so with severe limitations. Often they go through extended non-competitive “rebuilding” phases that last years (Oakland, Tampa Bay, Miami). Or they are only able to make the playoffs by winning weak divisions without big-spending teams (Cleveland, Minnesota). More fundamentally, there is a pretty hard ceiling on what these teams can accomplish in the playoffs: Other than the Marlins in 2003, no low-payroll team has ever won the World Series, and few have advanced even to the League Championship Series.

On the other hand, teams that rely on free agency to build their rosters tend to be more fragile, for these same structural reasons. These teams are usually older, because free agents are older, and more star dependent, since you can only sign so many free agents in a single off-season. The Mets, for example, are paying $86 million to Justin Verlander (age 40) and Max Scherzer (age 38); unsurprisingly, both have dealt with injuries this year. The Padres have over half a billion dollars invested in just two players on the left side of their infield, Manny Machado and Xander Bogaerts, both of whom are underperforming. None of these four players has been BAD, exactly, but they haven’t been nearly as good as you would have expected, and the teams are not built to withstand down years from these stars.

The ideal method of roster construction is to have a core group of young players you’ve developed, and then be willing to complement them with free agent acquisitions. But this is so obvious it’s hardly worth saying. Practically every team aims for this, but it is much harder in practice than in theory. There is no secret sauce, either money or “analytics,” that will magically build a World Series winner. You just have to do the stuff everyone knows you’re supposed to do even better than all the other people trying to do it.

Given this, the idea that there is some major competitive balance problem in baseball is total bullshit, a myth propagated by the ownership class who are invested in the idea that high baseball salaries make it impossible for “small market” teams to compete. By some measures there is TOO MUCH competitive balance in baseball, which hasn’t seen a repeat champion in 23 years and where every single team has made the playoffs at least once since 2015.

At the same time, there ARE teams that are perpetually non-competitive. But these teams are not constrained by their market size or any external factor — they are generally non-competitive by design. Sometimes it’s because they are trying to flee their city, like the non-Oakland Athletics, but more typically it’s just the epidemic of tanking that has plagued the sport in recent seasons. As I have written about many times, every baseball season now has multiple teams setting records for losses simply because the owner has no interest in fielding a good team.

In other words, to the extent that baseball HAS a competitive balance problem, it is because owners are choosing not to compete so they can raid their assets for cash or clout. As usual, then, owners are not the solution to a problem — they are the CAUSE of the problem.