Down With Job Interviews

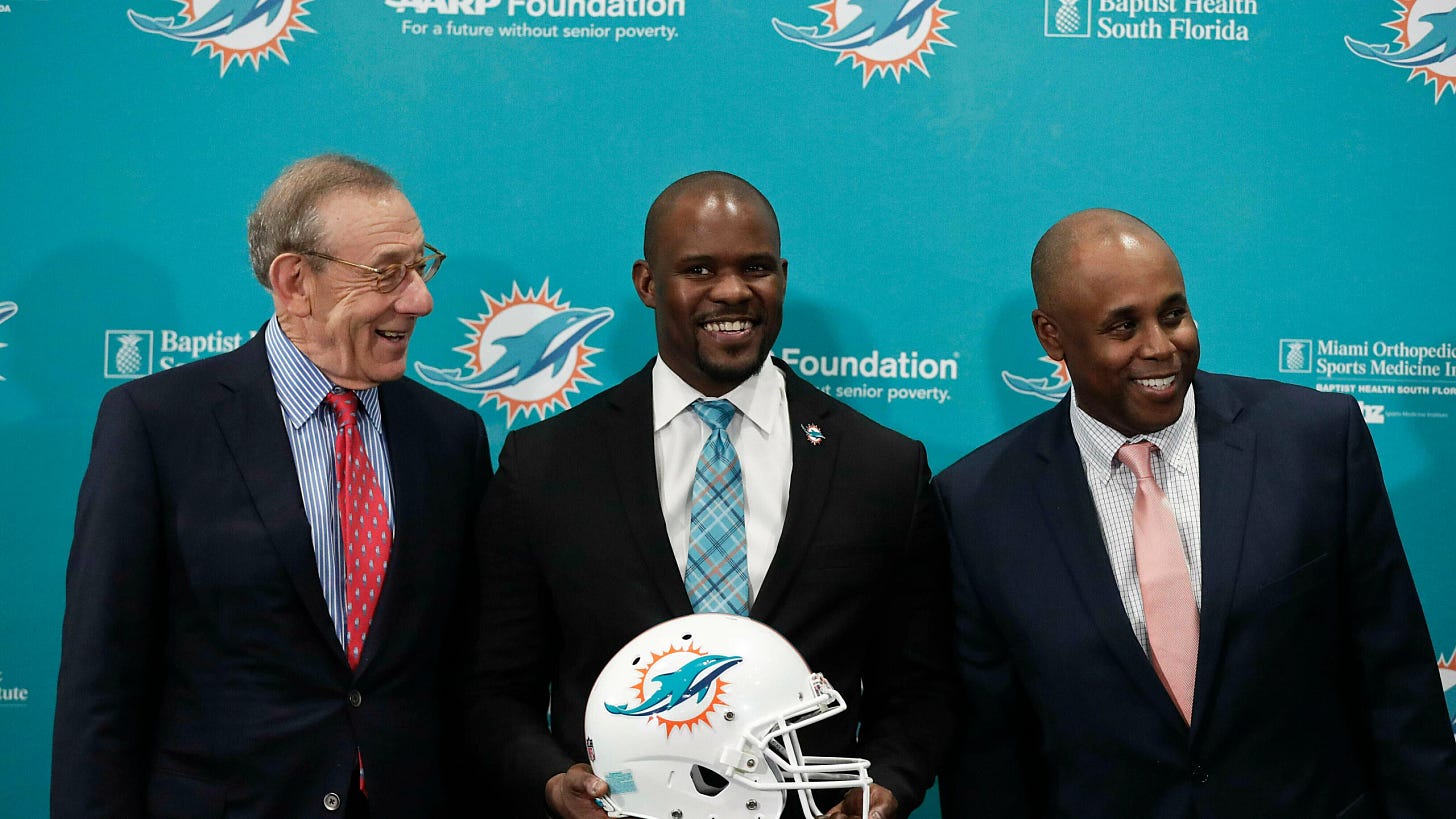

Of all the reactions to the Brian Flores lawsuit, the strangest has been the discourse around job interviews. Due to the specifics of the NFL’s Rooney Rule—which requires teams to interview Black candidates for coaching vacancies—and the details about this particular case, a great deal of attention has been paid to the exact timeline and nature of Brian Flores’ job interviews.

According to his complaint, Flores believes that the New York Giants had decided to hire Brian Daboll before interviewing Flores, based on texts he received from Bill Belichick. The Giants, on the other hand, insist that they only decided on Daboll after interviewing Flores, pointing out that Belichick does not work or speak for their team (a point undercut, pretty significantly in my view, by the fact that Belichick turned out to be right about who the Giants would hire). Similarly, Flores contends that the Broncos’ John Elway and Joe Ellis showed up an hour late and hungover to interview him in 2019, indicating that the interview was just a sham to satisfy the Rooney Rule. Elway insists that he was not hungover—he just looked like shit for unrelated reasons.

If what you care about is specific violations of the Rooney Rule, then these details are important—but that is really a small part of this story. If what you care about are the larger allegations of racism, discrimination, and unfairness, then would it really matter if Brian Flores’ interview had happened to be scheduled before Brian Daboll’s?

It’s as if we’ve all forgotten what job interviews are really like. In discussions like these, people talk about “job interviews” in the abstract, as if they are some pure, objective, and entirely merit-based part of the hiring process. But anyone who has been on or conducted a few job interviews knows that is hardly the case. In real life, job interviews run the gamut from “thorough and exciting” to “total waste of time for everyone involved.” Sometimes employers bring candidates in for an interview before they even know what they’re looking for in a position; sometimes they do it after they’ve already decided who they’re going to hire, but they want to create the illusion of a comprehensive process. Sometimes an interview is little more than a vibe-check, to see if a potential hire is crazy, or someone they can get along with. And sometimes employers approach job interviews with the purest and best intentions, but still hire the wrong guy because he happens have the specific charm necessary to come off well in the highly contrived setting of a job interview.

All of this is to say that job interviews are, at best, a very imperfect part of the hiring process. In fact, they are most susceptible to the biases of the employer, since having a good interview usually means getting along with the person conducting the interview. In the Giants’ case, the person picking the coach was newly hired General Manager Joe Schoen, who had previously worked in Buffalo—where the offensive coordinator was Brian Daboll! So regardless of when the Giants made their “final decision” on a Head Coach, Brian Flores was never being considered on equal footing.

As Flores’ lawsuit makes clear, these effects ripple out. Since General Managers are likely to hire coaches they’ve worked with before, the “club” of NFL Head Coaches becomes even harder to enter as an outsider. Since there are no Black NFL owners, they are less likely to hire Black team presidents, who are less likely to hire Black GMs, who are less likely to hire Black Head Coaches, who are less likely to hire Black coordinators, etc.

But the Rooney Rule is premised on the idea that this problem can somehow be solved at the interview stage. The idea is that if you guarantee Black candidates a foot in the door, they can prove their worth once there. And it seems to have had SOME effect: In the years between 1989 (when Art Shell became the first Black Head Coach in the modern NFL) and 2002 (when the Rooney Rule was adopted), there were 93 coaching hires in the NFL. Seven of those jobs went to Black candidates, or 7.5%. Since the owners implemented the Rooney Rule, there have been 134 hires (including Kevin O’Connell by the Vikings, which seems all but assured, but not including early reports that the Texans will hire Lovie Smith); 22* have gone to Black coaches, or 16.4%.

*For some reason, the Flores complaint says that only 15 Black head coaches have been hired since 2002. I’m not sure what the discrepancy is. Marvin Lewis was hired in January 2003, or less than a month after the Rooney Rule was adopted, so perhaps the Bengals were not subject to the rules under his hiring process. In which case the numbers would be 8 for the pre-Rooney Rule hires and 21 since. But I’m still not sure how they get to 15.

So there has been some improvement—it’s just that this improvement has not been at all commensurate with the prevalence of Black players in the league, or their interest in coaching jobs. Nor has it been enough to diminish the clear double standard Black coaches face in not only getting hired for, but keeping, these jobs. Because the Rooney Rule’s emphasis on job interviews was always misplaced, for the same reason it’s a mistake now to focus on the specific details of Flores’ job interviews. Even the Flores lawsuit falls into this trap at times, claiming that, “The Rooney Rule is also not working because management is not doing the interviews in good-faith,” as if there is some type of ideal, “good-faith” interview that would allow Black candidates to overcome the odds stacked against them.

There is, in any fight for equality, the hope that you can achieve it without disrupting things too much. Liberalism in particular clings to the notion that discrimination will naturally fade away because it is not in people’s self-interest, or because it is “bad for business.” The Rooney Rule’s premise is that you can force teams to consider more people, and that a team’s desire to win will take care of the rest. After all, what GM wouldn’t want to hire the best coach possible? And why would you artificially limit your talent pool by discriminating against Black candidates?

But it’s rarely that simple, especially in a field as vague, hard to quantify, and impossible to predict as NFL coaching. The Giants have insisted they chose Daboll because he was “the best qualified for the job,” but what does that even mean? If by “qualified” you mean experienced, then Flores is more qualified than Daboll. Perhaps they valued Daboll’s work building the offense in Buffalo, which was third-best in the conference this season—but then why didn’t they bother interviewing Eric Bieniemy, whose Chiefs have had the best offense in the conference in three of the four years since he became their Offensive Coordinator? Clearly, “best qualified” is not a precise term, and can be made to accommodate whatever gut-feelings, biases, and vibes a GM might personally have.

You can’t fix this problem with more or better job interviews—you need to change how hiring itself works. In other words, you need to take power away from the bosses. This offends people’s sensibilities, because one of the most sacred cows of capitalism is the absolute power of owners and bosses, especially when it comes to hiring and promotions. Occasionally you encounter a workplace—typically either a civil service job, or one that is heavily unionized—where the boss does NOT have absolute power in this regard: hiring or promotions come from some list, or are based on a complicated seniority system, or some other seemingly byzantine process. People complain about these things all the time—they often seem arbitrary and inefficient.

But the Flores case shows why these systems are necessary. It’s no accident that in any situation where workers gain some power, one of the first things they do is try to limit the hiring and firing power of bosses. It’s not just that bosses abuse power when those decisions are left to their whims and judgment—although they do. But even when they are trying to use that power correctly, they will inevitably end up letting their own personal biases cloud their judgment. So Joe Schoen hires Brian Daboll because he knows him and likes him, and decides that’s enough to make him the “best qualified” choice. That’s not because Schoen is an evil or racist guy, necessarily—there’s just a limit to what you can accomplish if you don’t take the power away from the bosses.

On this front, there are reasons to be optimistic about Flores’ lawsuit—and reasons to be discouraged. More on that later…