Wilt Chamberlain, Robert Nozick, and Egalitarianism

On the basketball legend’s cameo in political philosophy

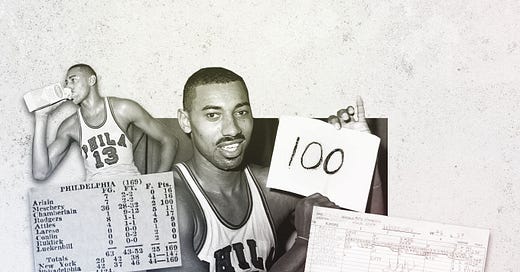

I. 100

Yesterday was the 63rd anniversary of Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game — that is, if you believe that game ever actually happened. You might not be aware of this, but there is a contingent online that believes Wilt’s 100-point game was faked. That since there is no video of it, it must have never actually happened. Initially I assumed this conspiracy theory was a joke, or just something believed by a bunch of zoomers who cannot fathom a major sporting event where there weren’t hundreds of cameras present. But there are actual NBA players who wonder about this, apparently, and the truth of that game has had to be reasserted several times in the last few years.

It says something about Chamberlain’s legendary career that his greatest accomplishment feels fictional. I must admit that the idea of one player scoring 100 points in a single game DOES sound pretty fake. The only person who has come anywhere close to that record was Kobe Bryant when he got to 81 in 2006 — but even that isn’t exactly CLOSE. Kobe would’ve needed a whole extra quarter to catch Wilt…

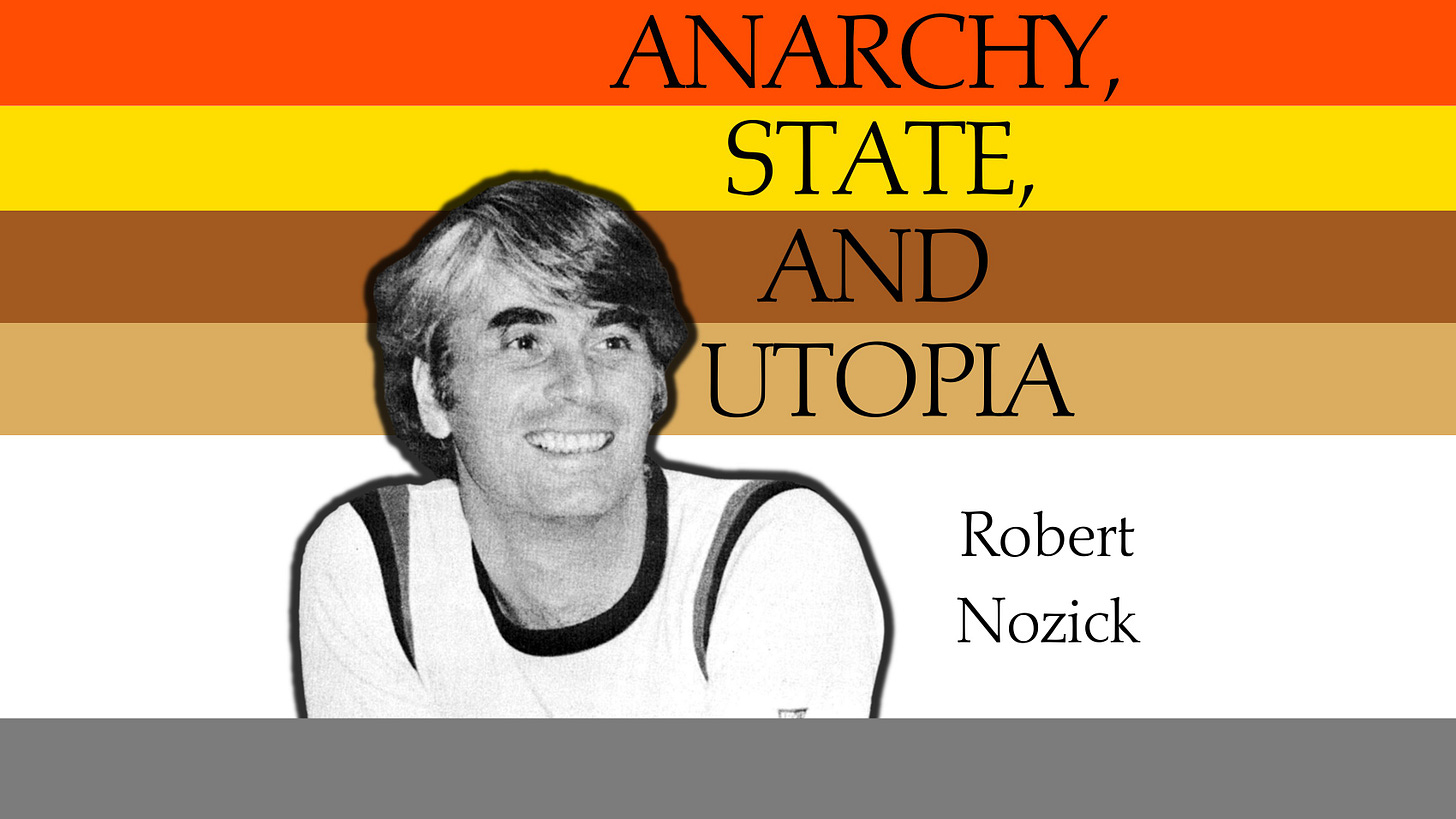

And it speaks to the kind of singular figure that Chamberlain was. The 100-point game is the most famous example, but there are so many facts about Wilt that speak to what a unique character he was. That he once AVERAGED more than 48 minutes per game.1 That he left college early to play for the Harlem Globetrotters for $50,000. That the NBA had to change the rules multiple times to accommodate his physical dominance.

Chamberlain is more than an athlete; he’s almost a Paul Bunyan figure in American history. So it makes sense that he would pop up in one of the most important political philosophy debates of the 20th century…

II. The Wilt Chamberlain Argument

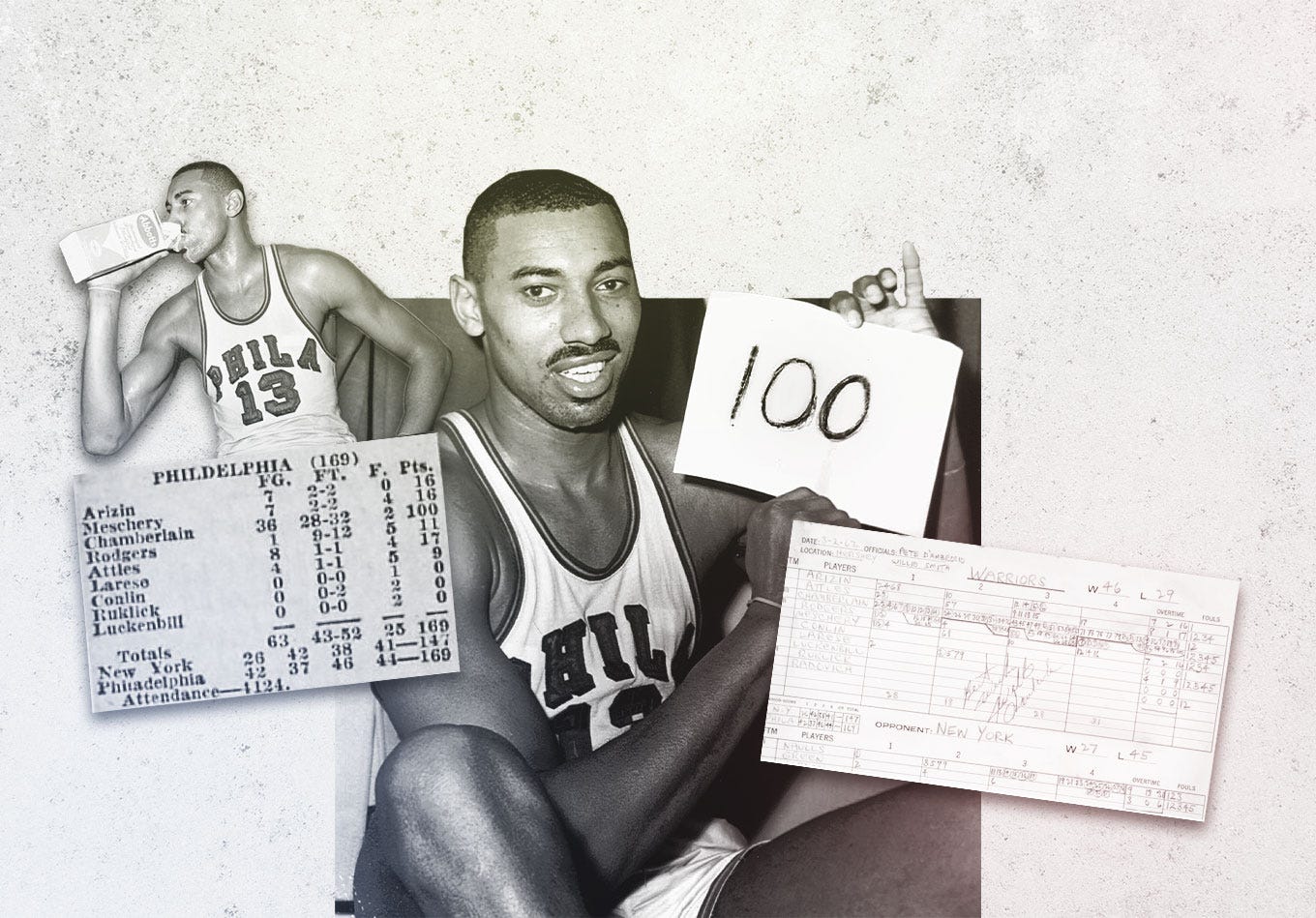

In 1974, a dozen years after the 100-point game and a year after Chamberlain’s NBA career had ended, a political philosopher at Harvard named Robert Nozick published Anarchy, State, and Utopia.

The book, which was named one of the 100 most influential books of the postwar period, is considered a foundational text for modern libertarianism, and one of its tentpole arguments is about Wilt Chamberlain:

“...suppose that Wilt Chamberlain is greatly in demand by basketball teams, being a great gate-attraction. (Also suppose contracts run only for a year, with players being free agents.) He signs the following sort of contract with a team: In each home game, twenty-five cents from the price of each ticket of admission goes to him… The season starts, and people cheerfully attend his team’s games; they buy their tickets, each time dropping a separate twenty-five cents of their admission price into a special box with Chamberlain’s name on it. They are excited about seeing him play; it is worth the total admission price to them. Let us suppose that in one season one million persons attend his home games, and Wilt Chamberlain winds up with $250,000, a much larger sum than the average income and larger even than anyone else has.2 Is he entitled to this income?”

This is a deceptively simple argument. In a sense, it’s just a star player signing a big contract, something we’re all familiar with. But Nozick is using it to explicitly reject egalitarian theories of justice. He is saying we cannot really evaluate the morality of a system based on whether it matches some preconceived theory of morality — like equality of income. Instead, we should look at whether the outcomes were arrived at freely and fairly. As he puts it, “Whatever arises from a just situation by just steps is itself just.”

The Wilt Chamberlain Argument stresses that everyone involved in the story is HAPPY with what’s happening. Chamberlain is happy to be playing and earning money. The team is happy to have him. The fans are “excited” and feel “it is worth the total admission price to them.” As Nozick clarifies elsewhere in the argument, nobody else is harmed by this exchange, and it is not interfering with other economic production in any way. So how can it be wrong?

You can likely see how quickly this line of thinking ends up in libertarianism. In order to prevent Nozick’s hypothetical, you would have to do something that offends basic moral intuitions. You would have to prohibit Wilt from playing basketball, or force him to play for less than customers would happily pay him, and both of those options seem obviously unfair. And from there you are just a few steps away from concluding that government interventions in the “free market” are generally unfair.

Depending on your perspective, Nozick’s choice of Wilt Chamberlain for his example is either pretty clever or pretty sneaky. After all, Wilt Chamberlain is a special player. He can score 100 points in a game! He can set the career scoring record! His nickname is literally The Record Book!3 Of COURSE people want to see him play more than other players, and therefore it seems eminently reasonable for him to be paid more than anyone else.4 Wilt was larger than life, obviously more than “equal” to the competition, and so trying to treat him “equally” feels foolish.

And once you grant that people like Wilt — that is, superstars who are obviously more gifted and talented than their competitors — exist and deserve greater compensation, you have created a justification for inequality that can apply more broadly. After all, there’s no telling who might qualify as a superstar because we cannot always anticipate or identify what skills will be valued by the economy. And, as Elon Musk has recently illustrated, rich people have no shortage of fans willing to die insisting that they are one-of-a-kind superstars, despite all evidence to the contrary.

III. Doesn’t Something Feel Off About This?

I first encountered the Wilt Chamberlain Argument in high school, and immediately I sensed that something was off about it. And not just because of the libertarian implications — it was mostly the basketball stuff that bothered me.

First of all, there’s this goofy idea of the “Wilt box,” that special box where these hypothetical fans put their 25¢ specifically for Chamberlain: “The season starts, and people cheerfully attend his team’s games; they buy their tickets, each time dropping a separate twenty-five cents of their admission price into a special box with Chamberlain’s name on it.”

Obviously nothing like this actually happens when you go to a basketball game. That in itself is not a problem — thought experiments often ask for some suspension of disbelief — but it’s a little confusing how all of this is supposed to work. Is this like a tip jar? Can I put more than 25¢ in it if I’m a particularly big Wilt fan? Shouldn’t he get paid more for weekend games, or rivalry games? What if I’m a fan of the visiting team, or I just want to see a basketball game and I don’t particularly care who’s playing? Do I still have to set aside a quarter just for Chamberlain specifically? And what about road games? Does Wilt just not get paid for those?

Nozick insists that every fan in this example pays the money “cheerfully,” as if all one million fans like Wilt exactly twenty-five cents worth, because he needs to skirt around these issues of how to precisely value Chamberlain. It’s one thing to say that, as one of the all-time greats, Wilt should be paid more than his peers; it’s another to say what that number should be. In order to accept Nozick’s argument that whatever number is arrived at by consenting adults freely agreeing to an economic exchange, we have to believe that everyone does so “cheerfully.” In reality, of course, many fans would grumble and complain, muttering about how Wilt was overpaid and greedy. At least some fans who might otherwise WANT to see a game won’t want to pay the new Wilt tax, or actually be unable to afford it. In other words, there WILL be losers in this arrangement, and the situation was not completely voluntary for them.

Nor is it voluntary for the other players, which leads to the other strange thing about this hypothetical. It always bothered me that the Wilt Chamberlain argument makes no reference at all to other players. Nozick even refers to him as “a great gate-attraction” as if he’s a panda at the zoo or something. But a star basketball player needs other players to be valuable. No fans are going to show up to watch a very tall man lightly drop a ball in a basket alone on the court…

Wilt needs teammates and competitors, and it’s not like you can just hire anyone off the street, at least not without losing fan interest. In other words, it’s not just hard to be precise about Chamberlain’s value; it’s also that his value is highly contingent, depending on the work of other people. So to treat Chamberlain’s contract as something that is negotiated in a vacuum, with no reference to how other players are paid — except to say that Wilt makes “a much larger sum… than anyone else” — feels obtuse.

Maybe the most glaring omission from Nozick’s thought experiment is the absence of any reference to wins and losses. You could say, I suppose, that team success is folded into the idea of Wilt as “a great gate-attraction,” since helping a team win games is a major part of what attracts fans. But Nozick has to skirt around this issue, because acknowledging wins and losses would mean acknowledging that Wilt’s success is not entirely within his own control, and that measuring his contributions to that success is more complicated than it might first appear. Indeed, that was something people argued about for Chamberlain’s whole career…

IV. The Real Wilt

In some ways, it’s funny that Robert Nozick used Wilt Chamberlain for his example. After all, he didn’t HAVE TO name a specific player to make his point — he could have just said “suppose a star player is in great demand,” etc. And yet he chose Wilt Chamberlain specifically, presumably because a player as sui generis as Wilt helped him make the case against equality.5

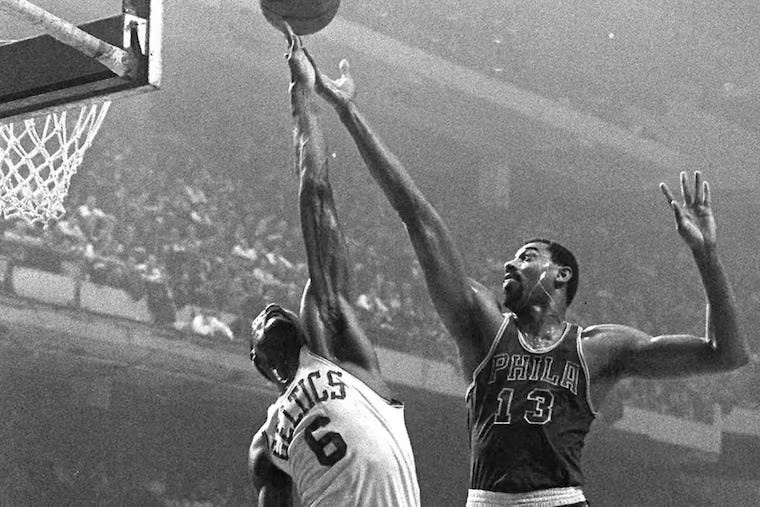

What makes this a little inconvenient for him is that, since Chamberlain was a real guy, he had a real life and a real basketball career that you could compare to Nozick’s example. And, surprisingly, real basketball fans did not see things as quite so clear-cut as political philosophers. In real life, fans and coaches and the media were constantly comparing Wilt, unfavorably, to Bill Russell. The argument was never that Chamberlain wasn’t a singular talent — everyone agreed on that. It was that Wilt wasn’t the winner Russell was. After all, Russell had not only won two national championships in college,6 but his Celtics teams eliminated Wilt’s teams from the postseason in five of Chamberlain’s first seven seasons.

In other words, despite his superior talent, Wilt Chamberlain was not actually considered the most valuable player in basketball for most of his career. In 1962, the year he scored 100 points in a game, AVERAGED more than 50 per, and played more minutes than are technically in an NBA season, Wilt did not win the MVP award, losing quite handily to Bill Russell. The Russell/Wilt debate set the template for a million sports arguments about team success versus individual success, about winning versus individual awards, about regular season dominance versus playoff performance, and basically every sports talk show argument we have today.

But the main point, at least as it relates to Nozick’s thought-experiment, is that even in a case as seemingly clear-cut as Wilt Chamberlain’s, even when the supposed value is as self-evident as being a giant on the court and scoring 100 points in a game, assessing an individual’s worth is never a simple thing.

Nozick would likely respond to this by saying that the opinions of fans and people in the media are not really relevant. As long as Wilt Chamberlain and the team agree to the terms of the contract, and as long as fans are showing up and putting their money in the Wilt Box, then that’s all that matters, in terms of deciding whether the situation is just or not. Of course, this invites another obvious objection to the Argument, which is that the market for Chamberlain's labor is not actually free.

You might have noticed that parenthetical at the beginning of Nozick’s thought-experiment: “suppose contracts run only for a year, with players being free agents.” Well, that’s a pretty big “suppose,” because at the time Nozick was writing it was not true at all. Free agency did not come to the NBA until 1976, two years after the book came out, and even then the free agent system was limited. If teams wanted to sign a free agent, they had to compensate the player’s old team; unrestricted free agency only began in 1988.

This meant that, for Wilt’s whole career, he was NEVER a free agent. It’s true that his unique talent gave him a degree of leverage most players did not have, and he was able to use that leverage to ensure he was usually the highest paid player in the league.7 He also engineered his own trade to the Lakers at the end of his career, helping get him his second NBA title. But not only was never able to negotiate a “Wilt box” — he never even had the opportunity to market his services to the highest bidder.

Surely Nozick would respond that this was wrong; he supports a player’s right to be a free agent, as evidenced by the fact that he included it in his argument. But it’s not clear what grounds he has to object. After all, he is refuting any patterned theory of justice, including a pattern that mandates free agency and one-year contracts — remember, according to him, “Whatever arises from a just situation from just steps is itself just.” If owners want to establish a league where teams retain a player’s reserve rights, then wouldn’t preventing them be just as much of an infringement on their liberty as preventing them from paying Wilt Chamberlain more than other players? Without state interference, free agency can only be won by players bargaining for themselves or withholding their labor.

As it would happen, Wilt Chamberlain tried both of those things! In 1958, after three years in college, Chamberlain left early because he was disillusioned with college sports and wanted to get paid like a professional. His reasons would be familiar to anyone paying attention to this debates in the seven decades since then:

“I need money to help my family. There are nine of us, six boys and three girls, and we’ve always had a struggle to get along… Coaches seldom try to sell you on education. If you want to study you can get a good education at any school and they know you realize this. So they try to sell you on other things – campus jobs, summer jobs, big athletic programs, affluent alumni. … They do a snow job on you.”

And yet the NBA had a rule prohibiting players from joining the league until they had been out of high school four years — a rule that would not bend for Wilt, even though the league had ALREADY awarded his rights to the Philadelphia Warriors, preventing him from bargaining with other teams. So Chamberlain went to play for the Harlem Globetrotters for a year, and even though he was well-paid — his starting NBA salary was actually a pay cut from what he was paid with the Globetrotters — and even though he enjoyed his time with the Globetrotters, the NBA never worried that Chamberlain wouldn’t eventually join the league. In other words, even taking his labor to another professional league didn’t get the NBA to change its rules.

Similarly, a few years later, Wilt negotiated an unusual contract with the 76ers that did NOT include a reserve clause. That was how Chamberlain ended up in Los Angeles at the end of his career. But even here, the Lakers had to send token compensation back to Philadelphia in a “trade” — the players acquired were not equal in value to Chamberlain, but it’s more than the 76ers would have received had Wilt been a truly free agent. In other words, even with Chamberlain’s unique contract, he could not get the NBA to fully break its rules regarding the reserve clause — free agency wouldn’t come to the league until after his retirement.

Speaking of Wilt’s retirement, even THAT was marred by restrictions on his ability to market his labor. After the 1972-73 season, Chamberlain’s final contract with the Lakers ended. An ABA team, the San Diego Conquistadors, offered Chamberlain $600,000 to be their player-coach. Wilt agreed, but the Lakers sued to prevent him from ever playing for the Conquistadors. Even though his contract had expired, and even though Chamberlain had not signed a new one, the Lakers claimed that by NOT signing a new contract, they still held an option on Wilt. A judge agreed, and Chamberlain never played in the ABA, thus ending his playing career.

All this just goes to show that, for as special a player as Wilt Chamberlain was, he couldn’t actually break down the rules owners had set up to suppress player salaries. As the history of all professional sports shows, the only thing that ever successfully contends with the power of owners is collective action by the players. That means a union, that means collective bargaining, and that means long-term contracts and rules about salary minimums and maximums. Put another way, that means rules that might restrain the liberty of individuals, especially stars like Wilt.

And yet nobody has benefited more from these rules than star players. As mentioned, Wilt Chamberlain was usually the highest paid player in the NBA, and at his peak he made $250,000 — about $1.6 million in 2025 dollars. But this season, the league’s highest paid player will make more than 33x that salary. Some of that is due to the growth of the league, but a lot of that increase is thanks to the power of the National Basketball Players Association.

In other words, collective bargaining and rules constraining individuals, rather than inhibiting individual liberty, actually EMPOWER individuals, including stars. Reality has a way of thoroughly undermining Robert Nozick’s thought experiment. Political philosophers love to say things like “Whatever arises from a just situation by just steps is itself just,” which sounds impossible to argue with. But applying it to reality either requires you to define “just situation” and “just steps” in ways that exclude basically all of normal life, or forces you to accept obviously untrue conclusions like, “Wilt Chamberlain was better off without a union.”

V. In Defense of Egalitarianism

Later in his life, Robert Nozick distanced himself from the libertarianism he espoused in Anarchy, State, and Utopia calling it “seriously inadequate.” He spent much of his later career not on political philosophy per se, but on complex philosophical logic puzzles.

Which really makes sense: It’s possible that the best way to read the Wilt Chamberlain Argument is as a kind of logic puzzle. Anarchy, State, and Utopia was written as a more or less direct response to John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, another one of the major postwar works of political philosophy, and things like the Wilt Chamberlain Argument are really ways of poking holes in Rawls’ arguments. At the risk of being somewhat reductive, Rawls wanted to preserve equality as much as possible, and Nozick’s book is essentially asking: How can you preserve equality between unequal people without extreme infringements on individual liberty?

And it’s a good question! His Wilt Chamberlain argument is persuasive because Wilt Chamberlain is so obviously not “equal” to the other players on the court. And while that is obviously an extreme example, Wilt is just a stand-in for the innumerable inequalities between individuals, not just when it comes to height and basketball prowess, but in terms of taste and interests and aptitudes and intelligence and so on and so forth.

The only real response is a rather boring one: Individual liberty is important, but it’s just one value among many and it’s basically meaningless without being considered alongside egalitarianism. Many Western thinkers seem almost embarrassed to talk about egalitarianism, worried that it sounds too Soviet or would require a kind of Harrison Bergeron-style enforced conformity. People in liberal democracies prefer to stress freedom of opportunity and rags-to-riches stories of individual accomplishment.

But egalitarianism IS really important, in a basic moral sense. It needs to be stressed that even if Wilt Chamberlain IS better at basketball — even if someone has more intelligence or more money or more education or more whatever — he is not more valuable as a human, and he should not be given the power to dominate or exploit or take advantage of others as a result of whatever natural inequalities might favor him. And while I’m tempted to say something excessive like “equality is MORE important than liberty,” the truth is, as the NBPA example shows, they usually go hand in hand. An unequal world is a world with less freedom, and it is a mistake to buy into the notion, propagated by capitalist ideology, that these two values are inherently at odds.

Egalitarianism might have no more forceful proponent in the last century than John Rawls, but even Rawls seemed to struggle with this. Although he is probably best understood as a socialist, he did not see himself that way, and is usually considered a defender of Western-style liberal democracies. But I think it’s this refusal to fully embrace socialism that opened his philosophy up to attack from Nozick.

Rawls’ Theory of Justice is full of attempts to parse exactly which types of inequities are justifiable and why, because there doesn’t seem to be any way to organize society without them. His efforts are elaborate and sophisticated, but not always convincing, and Nozick pretty skillfully pulls at the seams until they start to unravel. But the answer is not to abandon egalitarianism as a value. Just because it may be an unattainable ideal does not mean it isn’t worth pursuing.

The correct attitude towards inequalities is to try to eliminate them wherever they pop up — with the understanding that this won’t always be easy or feasible. Wilt Chamberlain is always going to be taller than the competition, and nobody is suggesting we cut him in half or kick him out of the league. But it might be a good idea to put severe limits on how much more he can be paid than the competition, even if that infringes on his individual liberty slightly. Because we ought to recognize that letting him get too wealthy risks entrenching certain inequalities, and opening up opportunities for exploitation and injustice.

If that means we have to abandon some of the traditional capitalist notions of private property, then so be it. Egalitarianism is a value worth preserving for its own sake, and once we start granting exceptions, the people who take advantage are not impressive superstars like Wilt — they are despicable robber barons like Donald Trump and Elon Musk and Miriam Adelson. Instead of trying to determine precisely which rich people have earned it and which inequalities are “just,” we should just put crude limits on the amount of inequalities we’re willing to tolerate as a society.

He played in every overtime period for his team, the Philadelphia Warriors, that season, and only came out of the game for eight minutes after being ejected with a technical foul against the Lakers. (The Warriors lost that game by one.)

LOL

Well, one of his nicknames. Chamberlain, like other exceptional American athletes such as Babe Ruth and Hank Aaron, has a truly wondrous panoply of nicknames: The Record Book, The Big Dipper, Wilt the Stilt, Big Musty, etc.

There is also the fact that Chamberlain was a Black superstar. Nozick was writing in the 1970s, before the latest round of identity politics, but there is still something obviously unseemly about arguing a Black man should get paid less so that mostly white fans don’t have to pay an extra quarter to watch him play…

I used to think that was the main reason Nozick picked Wilt Chamberlain for the example. But given that Nozick was working in Cambridge, MA, and Chamberlain was, in the 1970s, playing in the NBA Finals for the Los Angeles Lakers, I now suspect Nozick was also being a bit of a troll.

Wilt lost in the title game the only time his Kansas team made it the tournament.

The only real exception came after the 1965 season, when Wilt negotiated a raise to $100,000 — at which point his rival Bill Russell went to the Celtics and demanded HE be the highest paid player in the league, so Red Auerbach raised Russell’s salary to $100,001.